Is regenerative agriculture a leap of faith?

By Patrick Francis

A research survey into farmers attitudes towards regenerative agriculture by two University of Queensland academics refers to the controversial approach as “a leap of faith” and as “a contested world view rather than as a practice change issue”. Such a summary seems apt as Camille Page and Brad Witt research could not identify a definition for regenerative agriculture. On the contrary it found farmers identify a wide range of common practices irrespective of how their methods are interpreted by others investing in ideological and/or commercial opportunities.

With no strict definition for regenerative agriculture like the one for certified organic farming its advocates have opted to negatively portray other farming methods by describing them using unattractive terms such as “conventional”, “industrial”, “factory”, “intensive” , “productivist” and usually correlating the terms with “poor soil health”, “lower food nutritional quality”, “compromised livestock welfare” and “social harm” to minority groups.

The research authors have inadvertently fallen into the contested farming methods definition trap by stating in the introduction of their “Sustainability 2022” paper that “…modern industrialised agriculture has created space for the emergence of alternative models of food production, (and) the emergence of multiple perspectives around the nature and urgency of the solutions required.”

Such a statement assumes a definition of “industrialised agriculture” is somehow constrained in a time warp which prevents solutions emerging as agricultural science knowledge, technology, food and fibre consumer demand, ecosystem services and climate change evolve. That’s a nonsense assumption because the one constant associated with all farming over time is change.

Here are a couple of examples, there are hundreds more.

Prior to 1980 Australia’s northern pastoral cattle industry comprised the non-heat and low nutrition adapted Bos taurus (mainly British Shorthorn and Hereford) breeds. Today those breeds hardly exist except in composite genotypes dominated by Bos indicus breeds. Prior to the 1980s pastoral stations turned off five and six year old bullocks producing highly variable eating quality beef. In droughts many of these cattle died and if they survived the rangeland and water ways were degraded by over grazing. Since the introduction feedlots and the national feedlot Accreditation Scheme, pastoral stations turn off young cattle meeting a host of domestic and international market specifications with consistent high eating quality while ensuring high levels of animal welfare. This has become standard practice for young cattle where rangeland is of insufficient quality to ensure optimum growth rates.

Figure 1: Is the agricultural science and technology associated with northern Australia’s beef cattle genetics and rangeland management changes a version of “industrial/ factory agriculture” stuck in a pre-1990s time zone as some regenerative agriculture advocates suggest? Photos: Patrick Francis

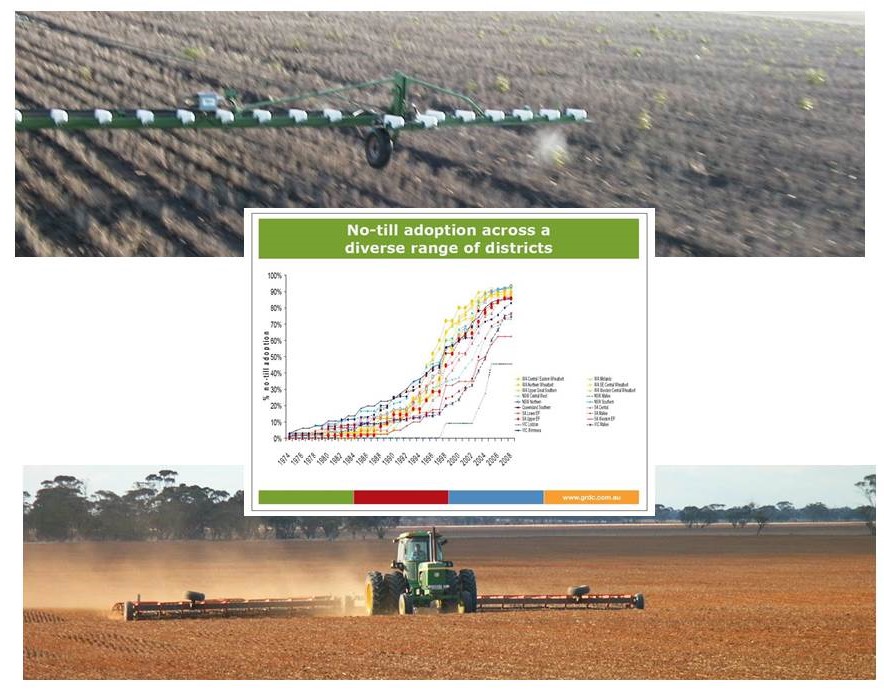

Prior to 1990 cropping across the so called wheat sheep zones was based around ploughing paddocks for weed control, disease control and soil moisture protection (fallows). Stubbles were burnt. Rotations were based mainly on cereals, fallows and annual clover pasture leys (sub clover and medics). Vast numbers of sheep were used to help control weeds, “clean” stubbles (of fallen grain), utilise pasture leys and ensure income diversification. In dry years and droughts crop and pasture ground cover disappeared, soil erosion by wind and dust storms were common. With rain soil erosion by water washed top soil and manure into waterways and dams.

Post1990 cropping practices changed with the introduction of machinery that could direct drill into stubble with weeds controlled by knockdown herbicides, particularly glyphosate. Crop rotations widened to include legumes such as peas, faba beans, chickpeas, lupins which fixed nitrogen in the soil and became disease break crops. Later canola became another break crop and part of the rotation. Stubbles were retained for ground cover protection while cleverly designed drills could sow through them without needing to burn. Sheep numbers declined (from 170 million in 1990 to 78 million in 2023) and flocks remaining became businesses in their own right rather than an auxiliary to cropping. Later precision farming emerged with satellite guidance technology allowing for controlled traffic operation on 2cm accuracy. Not only was ground cover kept to protect soil but compaction was removed as all wheels travelled on the same path year in year out. In header computer yield monitors and paddock nutrient budgets ensure precise application of fertilisers is applied across paddocks to avoid nutrient mining. Yields and soil health ecosystem functions improved even in dry years.

Figure 2: Terms to describe farming methods like conventional, sustainable, industrial, intensive, best practice, or even regenerative are meaningless without context. Over time farming methods change as knowledge and technologies improve. Cropping farmers shifted from soil tillage pre 1990s (lower photo) to control weeds to no-till once appropriate herbicides became available. Improved application technology enable farmers to reduce herbicide amount by targeting just the weed using this Weedseeker sprayer (top). Regenerative farming usually supports no-till and minimal herbicide use which is conventional best practice farming!

Is the agricultural science and technology associated with this cropping transformation a version of “industrial agriculture” stuck in a pre-1990s time zone?

Many outspoken advocates of regenerative farming would suggest that these two examples reflect “conventional, industrial or factory” farming which is socially irresponsible, degrades soil health, produces unhealthy food, and is bad for animal welfare. They fail to provide context to their criticisms, for instance confining young cattle to finish in 70 to 150 days in a feedlot has important soil and vegetation benefits compared with allowing the animals to survive on pastures with declining ground cover and constant threat of soil erosion and biodiversity decline. As well methane emissions per kilogram of carcase are far lower in young cattle finished in a feedlot when growing at 1.5 to 2.5kg per day compared with retaining them on paddocks where pasture quantity and quality has declined to the extent they may lose weight and take an additional year of grazing and methane emissions before they reach a suitable market weight.

The lack of context when using terms like industrial and factory farming is disingenuous because advocates dumb down the complex interactions involved in successful producing food and fibres in highly variable environments. They pick and choose components of methods and farm scale (what is an acceptable family farm size versus an industrial sized corporate) that suit their world view or ideology and criticise the parts they don’t agree with.

This is demonstrated by the UK based organisation Local Futures. In a blog it states “Regenerative has become a buzzword – but what does it actually mean? With big businesses jumping on the “regen” bandwagon, we need to maintain a clear idea about what a genuinely regenerative food system actually looks like. Vast monocultural farms – geared to export markets and almost always reliant on toxic chemicals – cannot truly be regenerative. Small-scale facilitates organic, lower-input farming practices.”

When farmers take a holistic approach to their operating methods those claiming to be regenerative have a demarcation decision problem, where does the so called conventional or industrial or factory farming begin for them and subsequently what farming scale and methods become unacceptable? The lines become even more blurred when climatic conditions impact farming programs. Does the regenerative agriculture livestock farmer refuse to sell young livestock to feedlots or finish them in a farm feedlot when pasture cover is threatened by drought? Does the regenerative agriculture crop farmer get out the plough to control weeds after a summer storm initiates widespread germination and risk soil erosion, soil carbon decline and increase diesel greenhouse gas emissions?

The answer to both these example question is no, most farmers who understand the complexity of biological systems and the give and take needed to manage them for positive holistic outcomes will take the suitable best practice action needed.

A regenerative agriculture educator alluded to the conundrum in a June 2021 article trying to answer why the program is not certified just like organic certification. Lorraine Gordon, Southern Cross University’s Director of Strategic Projects at the Regenerative Agriculture Alliance and Farming Together Program stated: “We cannot ‘certify’ regenerative practices because these practices are about continuous improvement and knowledge and therefore prescribing what is ‘in’ and what is ‘out’ goes against the basic principles of inclusiveness and continuous transformative learning and evolving with our landscapes. Regenerative agriculture is about being comfortable with ambiguity. Not trying to control things, instead letting ecological systems self-organise and accept that we don’t have all the answers, and probably never will. This also means not attempting to ‘define’ or ‘certify’ how regenerative agriculture is understood in different contexts.”

The danger looming is some regenerative agriculture advocates want to label some actions in such a negative way using terms like conventional, industrial, factory farming that divisions are created amongst farmers which are unnecessary unless ideologies are involved.

It’s the same decision dilemma for the private enterprises, non-government agencies, and government departments who throw their support and funding behind regenerative farming methods while also facilitating so called conventional, best practice, industrial or factory agriculture. The lack of clarity around what is regenerative agriculture versus so called conventional, best practice or industrial agriculture highlights the dilemmas involved trying to distinguish them. It supports Page and Witts research paper headline that regenerative agriculture is “a contested world view rather than a practice change issue”.

Figure 3A: Local governments and NGOs have adopted regenerative agriculture as a buzzword promoting it without any local context benchmarks or requiring on-farm monitoring for evidence of continuous improvement across soil health, pasture health and productivity, biodiversity, greenhouse gas emissions and abatement, livestock welfare, and waterway health.

Figure 3B: In the early 2000’s Environment Best Management Practice was developed as a means for farmers to monitor continuous improvement across all aspects of their properties environment and business and challenge existing farming practices. Despite wide spread government and NGO support adoption failed because it was farm context driven and required constant monitoring and data collection. Describing farming as regenerative is a simple and popular alternative for governments, NGOs, farmers, retailers and food consumers as it has no associated benchmarks and on-farm monitoring involved.

Page and Witts propose that regenerative agriculture is far more involved than what Gordon suggests “… is about being comfortable with ambiguity. ..not trying to control things”.

They said the divergence of goals between conventional and regenerative agriculture advocates suggests “…they also have distinct worldviews in terms of thinking about managing farmland and the relationship between farmer and nature.

“Transitioning from conventional agriculture to RA generally requires a transformation in farmer world view, mindset, values, beliefs, rules, practices, norms, and ideas about what being a ‘good’ farmer means in order to be sustained and successful.”

Figure 4: Organisations supporting regenerative farming are developing world views across a range of topics for participating farmers to support. All the nominated principles/outcomes are common across conventional best practice farming. Top: Textile Exchange. Above: Kering

Is it presumptuous of regenerative agriculture advocates and inappropriate for governments and businesses to judge the motivations and actions of others with various world views especially when it comes to identifying individuals social values like equity and justice?

Figure 5: Some businesses which promote regenerative agriculture have narrow world views which are used to convince customers that the farming methods behind their products are good for them and for the planet. Providing context around managing complex biological systems in highly variable environments and soil types is ignored. This example from the USA Dr Zach Bush’s web site promotes regenerative agriculture with particular emphasis on farming without using herbicides particularly glyphosate and other pesticides which it claims are the major cause of an “…an explosion of chronic disease” amongst Americans.

Farming and environment context missing

Page and Witts research uncovers a key omission in the world view transformation needed to achieve regenerative agriculture, there is a lack of context around production and environmental considerations.

“Many practices associated with RA are promoted without consideration of regional or individual farm context: yet the efficacy of many RA-promoted practices are highly context dependent and unlikely to lead to the same benefits in all contexts. Thus, the proposition of a universal solution that could be applied in all agricultural contexts is potentially misleading given the significant diversity of global agri-ecosystems and farm systems, and the spatial and temporal variation of the environmental and social issues associated with agriculture.”

Figure 6: Context around world view terminology like industrial, factory, best practice farming is critically important before judgements should be made. For instance beef cattle can be removed from rangeland to finish in feedlots be they small on farm or large corporate owned lots but the outcomes for preventing rangeland degradation, insuring livestock welfare, and producing high eating quality beef are similar. Numbers of cattle on feed in Australia have increased since the 1990s while the total beef cattle population has remained steady. What is the impact of the increasing use of feedlots to finish cattle on grazing land health and biodiversity as well as on methane emissions? Photos: Patrick Francis; Graphs: Australian Lot Feeders Association & MLA.

Greenwashing with regenerative agriculture

Another important issue they raised is the increasing use of regenerative agriculture term as buzzword for greenwashing.

“Buzzwords are popular concepts with a strong performative aspect that combines a strong belief in the concept with the absence of a clear definition. Buzzwords sound intellectual and scientific, but their vague meanings tend to suggest that the concept is beyond the reach and understanding of the average person and so is best left to ‘experts’.”

Across all media formats farmers, particularly those selling direct to processors/consumers, are increasingly describing themselves or are described by journalists as “regenerative” without substantial evidence being presented about outcomes being different over time other than vague references to reduced use of artificial fertilisers and herbicides. For farmer and landcare groups applying for project government funding it is highly likely that including references to supporting regenerative agriculture will be critical for success.

Figure 7: Farmer groups are increasingly identifying as “Regenerative” as it is a powerful buzzword which seems to be associated with government and NGO sponsorship. Not all groups have gone down this naming path. The Loddon Plains Landcare Network advocates for a “Sustainable Agriculture Strategy” but mentions on its web site that “LPLN Inc. is a leader in Sustainable and Regenerative Agriculture in Central Victoria”, the differences if any between the two are not detailed.

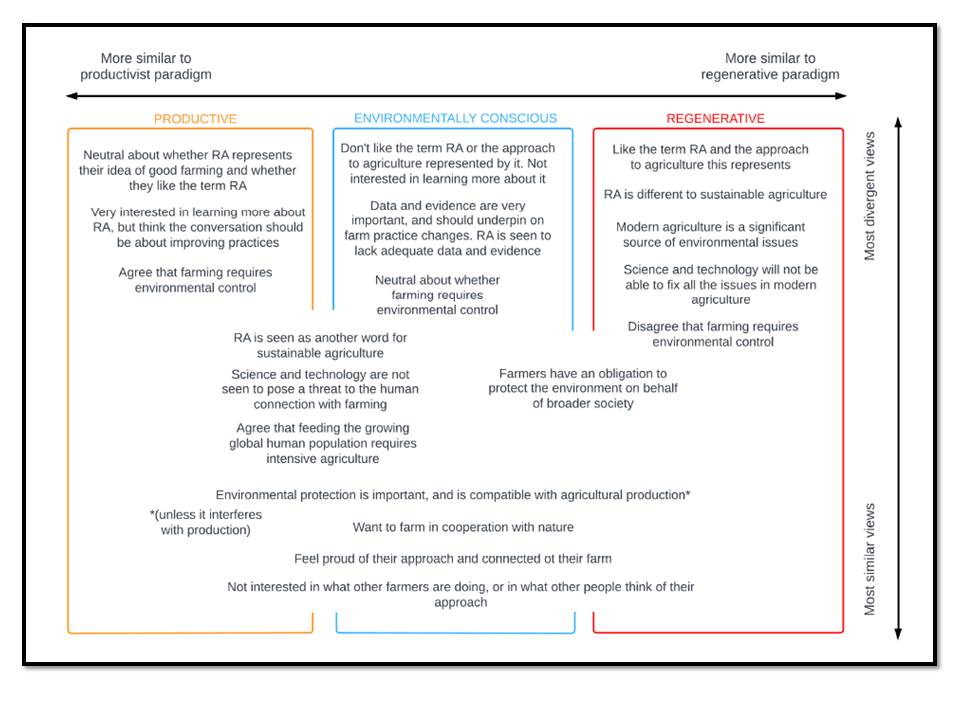

What regenerative agriculture actually is on farm seems from Page and Witts research to be a far cry from some outspoken advocates’ world views. Their interviews found a continuum of farming methods across the conventional farming (also called productivist) paradigm and the regenerative farming paradigm. In practice there is a great deal of commonality, not barriers, figure.

Figure 8A: The outstanding feature of the Page and Witts research is in this diagram which demonstrates most farmers are on the same operating and learning trajectory with respect to enhancing the environment, protecting animal welfare and working with nature.

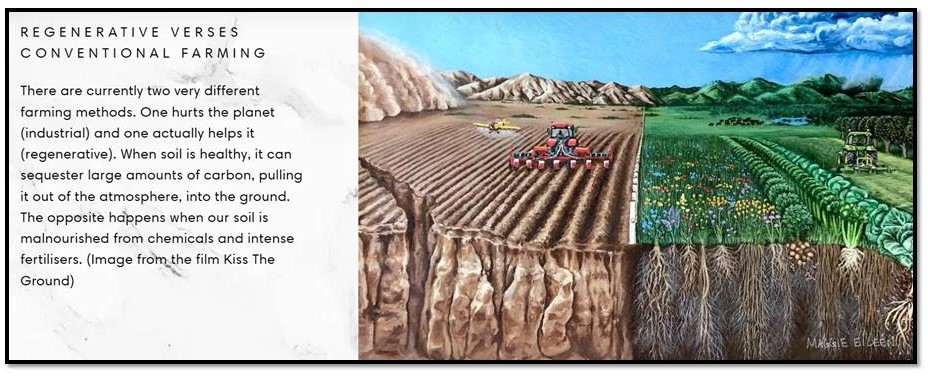

Figure 8B: Some of the publicity around regenerative agriculture promotes a strict dividing line between it and conventional farming. Regenerative farming is all good and conventional farming is all industrial and bad. This creates division between farmers and is untrue as Page and Witts found. Source: The Good Farm Shop.

The three particularly important common approaches identified in the survey which challenges the premise that regenerative agriculture farmers have an exclusive world view about farming are:

* Environment protection is important and is compatible with agricultural production.

* Want to farm in co-operation with nature.

* Farmers have an obligation to protect the environment on behalf of the broader society.

Even a regenerative agriculture organisation the New Zealand Merino Company which has developed an exclusive RA trade mark called ZQRX notes on its web site “It’s important to remember that regenerative agriculture will look different from farm to farm – It is not prescriptive and there is no one size fits all solution..”

Take home message

The results of the Page Witts survey indicates that amongst farmers themselves what their methods are called means very little, it is the direction they are heading and outcomes achieved in conjunction with nature that is important. The issue many farmers who identify as regenerative may have is they are making a leap of faith and inadvertently aligning themselves with ideologues with extreme world views whose agendas lack individual farm context and could actually be negative for continued production of high quality food and fibre in conjunction with improved ecosystems services and reduced greenhouse gas emissions.

Figure 9: While there are different interpretations around terms like conventional or industrial agriculture some advocates for regenerative agriculture have specific agendas such as Carbon 8 which has initiated a National Regenerative Agriculture Day promoting a ban on pesticides in agriculture. Source: Carbon 8

Box story:

Definitions of industrial agriculture?

Google search definitions provide no context around variations across the world regarding environments, soils, climate, human population, food customs and demand, food quality, greenhouse gas emissions, and biodiversity:

* Industrial agriculture is the large-scale, intensive production of crops and animals, often involving chemical fertilizers on crops or the routine, harmful use of antibiotics in animals (as a way to compensate for filthy conditions, even when the animals are not sick).

* Industrial agriculture refers to growing plants and raising animals at large scales for the purpose of maximizing food production. To achieve this goal, farms rely on synthetic chemical inputs to boost productivity and—when possible—mechanization of manual processes.

* Industrial agriculture is the intensive farming of live animals and crops for the mass production of food and food by-products. For much of human history, agriculture relied on countless small farms to produce a wide variety of foods. But now, small independent and family-run farms use only 8% of all agricultural land.

* Despite its dominance, industrial farming is not the best way to feed the world because it harms animals, people, and the environment. What is industrial agriculture? Industrial agriculture refers to growing plants and raising animals at large scales for the purpose of maximizing food production.

* Human agriculture has existed for about 12,000 years, and industrial farming is less than a century old. But the latter has become so prevalent that sustainable farming practices are now sometimes branded “alternative.”

* Industrial agriculture is the intensive farming of live animals and crops for the mass production of food and food by-products. For much of human history, agriculture relied on countless small farms to produce a wide variety of foods. But now, small independent and family-run farms use only 8% of all agricultural land.

A different perspective from an Australian agronomist:

Broadly speaking there are three main livestock production systems in Australia: grazing, mixed farming and industrial. In beef production, industrial systems are often the final component of a stratified system starting with grazing or mixed farming and finishing with feedlots for feeding to meet market specifications. Peter Simpson, a career agronomist with NSW Agriculture 2002

Figure 10: Regenerative agriculture is now an appealing buzzword for promoting brands aligned with world views their owners feel customers will associate with. Above: New Zealand Merino Company now has regenerative wool fibre platform.