Record rain and lamb growth highlights for spring 2022

By Patrick Francis

It’s been a spring like no other ever experienced with four consecutive months rainfall above 100mm. It started in August, included the greatest monthly rainfall on record in October with 238mm and ended with 134mm in November. As a result paddocks were waterlogged for six weeks from early October to the end of November. Our trickle flow Sandy Creek turned into a raging torrent on four occasions obliterating our stone vehicle and livestock crossing each time.

Figure 1: Sandy creek is usually a trickle but 48 hours of rain on 12 and 13 October saw it turn into a torrent. In our history it has never been as high as shown in the right photo. Photos: Patrick Francis

Despite the rainfall, we had our a highly successful lambing starting 20 August and finishing 15 September with 95% of lambs dropped in the first three weeks. There were no weather related lamb mortalities with pregnant ewes depastured across five paddocks containing 2000 to 3000kg dry matter per ha pasture usually 15 to 25cm high, three days before the due lambing date. The lambing paddocks are rested from grazing in mid-May to mid-August to ensure sufficient high quality pasture is on hand during lambing and internal worm larvae on pasture is minimal.

An unusual feature during lambing this year was far fewer sighting of foxes. Only 7 Foxoff baits were taken compared to 74 in 2021. No foxes were seen in lambing paddocks at night. Our lambing paddock hygiene might help in this regard – all afterbirth is collected as soon as possible after each ewe has lambed and any lambs born dead (suffocation in afterbirth) are also quickly removed. These membranes and carcases are incinerated.

As part of our data collection for Sheep Genetics Lambplan all lambs are checked and weighed within 12 hours of birth. At the same time we make an assessment of each ewe’s maternal behaviour score (MBS) by noting how close she stands to us as we check and weigh her lambs. This is an important trait associated with mothering ability meaning ewes are less prone to being disturbed and so there is less likelihood of lambs dying by being separated. High MBS ewes stay in their birth zone for five to eight hours giving greater chance of close bonding with their lambs. 95% of our ewes have an MBS of 1 meaning they do not move more than 5m away from us and most stand next to us.

Our lamb birth weights are interesting given pregnant ewes have access to large quantities of pasture irrespective of carrying singles, twins, or triplets.

Singles average birth wt 4.67kg; range 4.0 to 5.4kg.

Twins average birth wt 4.19kg; range 3.1 to 5.5kg.

General ewe husbandry recommendations are for a higher level of nutrition being available for ewes carrying twins/triplets compared to ewes carrying a single lamb. The rationale being too high a level of nutrition for singles will lead to increased dystocia risk (difficult births) due to bigger than average lambs. Our experience does not support this as dystocia level is low among single bearing ewes, and when it happens is not necessarily due to lamb size but to mal-presentations such as front leg back and breech births. It is the reason why we don’t pregnancy scan which is usually done to identify pregnancy status and to allow different levels of ewe nutrition management based on number of foetuses carried.

The most common animal husbandry reason behind pregnancy scanning is the fact that for most sheep farmers, pasture availability during winter/early spring is limited and often inadequate to meet the nutritional requirements for pregnancy and early lactation. In such situations, the farmer can provide twin bearing ewes with additional pasture or concentrate supplement compared to what’s needed for single bearing ewes. We avoid this problem by adopting a year round livestock paddock carrying capacity which allows us to grow sufficient pasture in June, July and August to support the nutritional needs of all ewes irrespective of carrying singles or twins. Similarly “saved pastures” from late May for lambing ewes ensures adequate nutrition irrespective of litter size through lactation.

A December 2022 Australian Wool Innovation review of pregnancy scanning concluded “The main benefit of scanning is that it enables sheep producers to better meet the nutritional requirements of ewes of different litter sizes, including empty ewes, thereby increasing marking rates.”

This year we analysed lamb growth rate per day to weaning taking account of average weight of lamb weaned per ewe and actual growth rate to weaning, table 1. We found the ewes are producing more kilograms of lamb at weaning than ever before. An important consequence of this is that the fixed methane emissions associated with each ewe per year are spread over more kilograms of meat lowering the greenhouse gas emissions intensity of Moffitts Farm lamb.

Table 1: Growth of lambs per day per ewe to weaning has been steadily increasing in the Moffitts Farm Wiltipoll flock which makes an important contribution to reducing the flock’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Faster weight gain post weaning by finishing lambs on high quality, high digestibility pasture mixes based on chicory, perennials clovers and summer active perennial grasses further reducing greenhouse gas emissions intensity from the flock.

Technology

This year we introduced a new piece of zero emissions technology to assist us during lambing, an electric trike. Such a machine was new to us but with some web research the right trike was found in WA. Up to this year we have been carrying buckets for weighing lambs, picking up afterbirth, and emergency birthing equipment around each paddock. Because of the amount of equipment is usually meant checking MBS and birthweight on one visit and returning to pick up afterbirth. The electric trike meant everything could be carried and done together.

The electric trike features are its quietness, its stability, its fat tyres which meant it easily traversed wet paddocks and long pasture, and its ability to carry equipment. With a bit of ingenuity a system was developed which meant weighing could be done by one person even with twin lambs, figure 2. This year we introduced a traditional 10kg Salter clock face spring scale rather than an electronic luggage scale. We found the electronic scale was too unreliable, turning itself off at the wrong time and regularly running out of battery power.

Figure 2: The electric trike was set up to carry a scale, a small pen to temporarily hold up to three lambs as each one waited its turn, a bucket for afterbirth and a bag for emergency equipment. Photo: Patrick Francis.

We also developed another labour saving and welfare stress reducing role for the trike – to transport lamb(s) back to the shed for emergency treatment. With a low trailer attached we found the ewe was not disturbed by her lambs being placed in the pen. She could easily see and hear the lambs and quietly followed the trike without hesitation, Figure 3.

Figure 3: With a low trailer attached carrying a highly see through cage, ewes had no hesitation following the noiseless trike.

Ram lambs retained

This year for the first time we decide to retain 12 ram lambs for potential sires for ourselves and other shedding flock breeders. We are becoming increasingly confident in the genetic performance of progeny from our highest Lambplan index ewes. We make the selection at lamb marking based on each potential ram’s dam index and its own performance to that age. A second selection of the retained rams is undertaken at approximately 10 weeks of age based on their growth performance which by this age is less influenced by their dams milk production, their conformation, and their fleece shedding ability. We are looking for ram growth rate which is at least 50% above the average of all their siblings, and obvious shedding. We contend that Wiltipoll rams suitable for the high rainfall zone must be full shedders.

Pasture topping machine comparison

In autumn I evaluated if topping pasture with a mulcher produced different recovery growth outcomes to topping with a slasher. We traditionally use a slasher but the idea of leaving windrows of cut pasture especially in high dry matter paddocks is a disadvantage for pasture growth under the windrow. A mulcher on the other hand leaves the cut pasture spread evenly over the swath width. The mulcher I used was 1.5m wide, the same width as the slasher. The most obvious difference between machines was the extra power needed for mulching and the slower travel speed. This was a negative for the mulcher as far as greenhouse gas emission were concerned – it means more diesel use per hectare.

Figure 4: Pasture topping via mulching left, slashing right. Outcomes for pasture growth were the same but mulching required more diesel use per hectare. Photo: Patrick Francis.

As far as the pasture recovery was concerned between the two topping methods I could not determine any difference in subsequent months. My conclusion was I will stick with the slasher for topping as it means lower greenhouse gas emissions per hectare.

New fertiliser demonstration

Earlier in the year I found out that Incitec Pivot is building a new fertiliser plant west of Melbourne to produce a range of biofertiliser granule mixes using heat treated poultry litter as the core ingredient to provide around 10 – 20% carbon. A range of different formulations are being developed by adding specific inorganic nutrients such as phosphorus, nitrogen, potassium and sulphur to lift nutrient density of the base poultry litter.

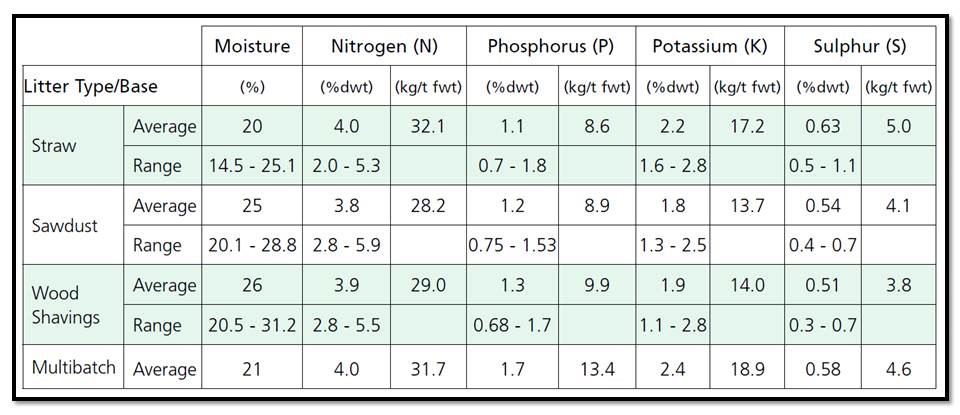

This product can have implications around Scope 2 (on farm) and Scope 3 (transport to farm) diesel greenhouse gas emissions. Poultry litter is not nutrient dense containing around 4% N, 1.2%P and 2.0%K and 25% water, so large quantities need to be transported to the farm and spread on farm to meet paddock nutrient budgets, Table 1. By adding inorganic nutrients into the poultry litter based granules, the quantity of fertiliser transported to the farm then spread to meet nutrient budgets is significantly reduced. The moisture content of granules is less than 4%.

Table 2: Chicken litter composition varies depending on bedding material used. Source RIRDC litter survey 2010.

For instance a farmer adding 30kg P per ha would need to spread approximately 2.5 tonnes per ha of poultry litter but with a 10% P biofertiliser granule just 300kg per ha. On the other hand the granule (<4% moisture) will deliver around 30 – 60kg/ha C while the two tonnes (25% moisture) of poultry manure will deliver around 400kg C per ha. The longer term impact on soil health and extended nutrient availability by providing extra carbon for soil microorganisms needs to be evaluated on a paddock by paddock basis bearing in mind existing soil organic carbon levels.

This biofertiliser being a granule makes it suitable for use in seed drills and conventional spinner type fertiliser spreaders, figure 5. The company provided a hundred kilograms of two formulations B5 (N:P:K:S:C ; approx 9:9:10:1:14) and E1 (N:P:K:S:C; approx 14:9:?:?:?) to run a demonstration at three different rates and three replicates in two different pasture types – chicory/clover/ryegrass and multi-species perennial grass dominant pasture. The plots were prepared and fertiliser spread in mid-June at rates of 100, 200 and 400kg/ha.

Figure 5: Incitec Pivot’s new poultry litter based biofertilisers are in a granule format which means they are suitable for spreading in conventional spinner machines. Photo: Patrick Francis

The 4 square meter plots were visually monitored through July, August, September and October. Only the 400kg/ha rate of both formulations showed any pasture growth response, but it was not uniform across the replicates. By early August with no grazing some of the highest rate plots had grown approximately 2500kg DM/ha versus the lower rates and surrounding control showing approximately1500kg DM/ha, figure 6. By mid October there were no discernible differences between the two products and between treatment rates and the control.

Remembering with well above average rainfall in August, September and October, it is likely organic matter mineralisation in the soil provided all plots with sufficient nutrients for optimum pasture growth in late spring and the additional nutrients from the two treatments became insignificant. It is also important to note that soil organic carbon levels in the two paddocks is high at 4 – 5% so small additions of organic carbon per hectare from these biofertilisers is unlikely to increase nutrient cycling via microorganisms

An alternative explanation is the soil nutrient content across the two demonstration paddocks was sufficiently high that the addition of extra nutrients particularly P and N was not required. In another year with lower winter and early spring rainfall a more obvious response could have been achieved.

Figure 6: Responses to the new poultry manure based fertiliser were variable across sites. This 400kg per ha E1 biofertiliser plot had grown around 2500kg per ha DM after 8 weeks (7 August) compared with the surrounding control at 1500kg per ha DM. The response was most obvious across perennial ryegrass and white clover species. Chicory is not a winter grower. Photo: Patrick Francis.

Wildlife and environment

It has been insightful to read paleontologist Steve Brusatte latest book “The rise and reign of the mammals”. The introduction made a statement which highlighted just how important Australia’s mammals are in the evolution of the species. It states “All modern-day mammals belong to one of three groups, the egg laying monotremes like the platypus (and echidna); marsupials like the kangaroo and koala (and wombats) that raise their tiny babies in pouches; and placentals like us, which give birth to well-developed young. These three types of mammals though, are simply the few survivors of a once verdant family tree which has been pruned by time and mass extinctions”. It is a privilege to have all three types of mammals on Moffitts Farm and in the Macedon Ranges Shire. Surely it highlights why humans as co-mammals should take better care of all animals in our environment.

The major wildlife development over the past 12 months has been return of wombats to our riparian zone along Sandy Creek. These animals, seem to have become permanent residents and are constantly moving back and forth along the creek, crossing Moffats lane to access the riparian zone on my brother’s farm. Unfortunately, this movement between farms is resulting in animals being killed by vehicles, with three wombats killed in one month in May/June, figure 7. We are continuing to lobby the Department of Transport to reduce the default maximum vehicle speed on the lane through a wildlife hotspot from 100km/hr to 50km/hr . Currently the Department’s guidelines for setting speed limits on rural roads makes no mention of wildlife as a factor to be taken into consideration.

Figure 7: While Moffitts Farm is a Land for Wildlife registered property, there is no associated protection of wildlife on adjacent minor rural roads where the Department of Transport default maximum speed is 100km per hour, far to fast to prevent collisions with wildlife. Photos: Patrick Francis

Koalas are rare and endangered in the Shire, our wildlife camera captured one walking along our front drive in April. Another was sitting on Moffats lane in November, figure 8. Part of our tree planting program across the farm since 1990 has specifically include manna gums (E.viminalis) as they a key diet for koalas. The fact we continue to koalas visit Moffats Farm suggests this approach is producing a host of co-benefits for the environment.

Figure 8: Koalas are rare but continue to visit Moffitts Farm. Photo (left) Doyle Dertell.

So informative and interesting. You obviously have a science background with your aptitude for detail.

We purchased a flock of 20 Wiltipoll ewes last year for commercial purposes from Kilmore, a deceased estate. We have 40 acres at Upper Lurg, northeast Victoria. We purchased a ram in January from a breeder at Tabletop. 33 healthy lambs were born between 27thJuly and 20th August. No issues with birthing…3 sets of triplets, 2 single births and the rest twin births.

The heavy rainfall has not affected them as they can move to high ground and have good protection from wild weather.

When should I separate them from their mothers as most are still suckling but appear to be growing a well.

Hello Margaret,

Interesting to read you had such a good lambing. Your experience highlights what we have seen in many Wiltipoll flocks, the breed has excellent fertility with ewes being excellent mothers. As for lamb age at weaning the animal husbandry data suggests there is no point extending it beyond 12 weeks of age. The reason is ewe lactation peaks around six weeks post birth, then steadily declines and by 12 weeks of age is around 20% of peak lactation. So lambs particularly twins and triplets are receiving very little nutrition from their dams yet they are constantly following them and “looking” to suckle. I suspect that is a nutritional stress on the ewe especially going into summer as pasture quality declines. I also suspect it is not helpful to her lambs whose grazing behaviour is somewhat impacted by their attachment to their dams. Once weaned lambs settle down in their own flocks and develop behaviour based around grazing. From a nutritional point of view the requirement of a dry (weaned) ewe are significantly lower than those of weaned lamb being grown at 200 – 350 grams per day to meet reach a target carcase weight. Weaning provides the opportunity to meet both classes nutritional demand. For us, weaned lambs graze the highest quality perennial pastures we have – chicory, white and red clovers, and ryegrass, to optimise growth rate per day. In contrast ewes are grazed on our “standard” and often poorer quality perennial grass pasture. They become our pasture growth managers grazing at high stocking rates (up to 100 dry sheep equivalents per hectare) for short periods (up to 7 days) and constantly rotated to control the prolific growth of less desirable species, or to control pastures is agroforest blocks or rocky paddocks which cannot be mechanically topped. If weaning is delayed longer than an average of all lambs being 12 week old, the greatest risk is to ewe condition score possibly declining during an extended lactation and subsequently there is difficulty lifting condition score (if below 3) to optimise joining weight for March/April mating. It is a nutritional fact that maintaining condition score at 3 or higher is easier to achieve than trying to feed a supplement to ewes in autumn to bring them from below condition score 3 back to condition score 3.

On ewe condition scores there is another factor we keep in mind, and that is each ewe’s genetic resilience to maintain their weight during lactation in our relatively cold and high rainfall environment. It is likely that resilience is heritable, so we condition score all ewes at weaning and those that have significantly dropped below condition score 3 due to lactation demands are noted and their lamb performance checked. A poor condition score at weaning may be used to cull a ewe (there are other factors also taken into account) if it is also associated with her progeny being significantly below average weaning weight. What we are looking for are genetic “curve benders” ewes that maintain their body weight during lactation and produce lambs with above average weaning weights. These ewes are the one that will get back in lamb early in the mating period and continue to produce high growth rate performing lambs. We also take a lamb’s mother’s resilience at weaning into account when selecting replacements (ewes and rams) as future breeders. The final point to make about these “curve bender” ewes is they are the ones which lower our flock greenhouse gas emissions per kg of carcase weight sold. Flocks with animal husbandry strategies which lower emissions will become increasingly attractive to red meat retailers and consumers.