A rural land use strategy with no future

Feedback on the Macedon Ranges Shire Council draft Rural Land Use Strategy

Introduction

In August 2021 Macedon Ranges Shire Council released a draft Rural Land Use Strategy for comment by rate payers. My submission is a lengthy document relating the science involved in agriculture, climate change, and ecosystem functions as well as personal experiences of landholders in the district, to land use. This article provides a summary of my findings. The images in the submission are included to highlight what is missing from the draft strategy. UPDATE DECEMBER 2022. Council voted to end the Land Use Strategy project due to its inadequate coverage and look at it again sometime in the future. Patrick Francis

The Draft Rural Land Use Strategy takes a traditional approach to land use across the Macedon Ranges Shire’s 135,000 hectares farming and rural conservation zones. Importantly it provides a policy framework to protect this area from development into rural living and residential zones which would mean total loss of rural land for future agriculture use and for critical peri-urban ecosystem functions such as water quality, flora and fauna enhancement, climate change mitigation and landscape amenity.

Apart from this important positive policy setting, the Draft Strategy fails to identify the land use initiatives needed across the two zones to meet the challenges the area faces over the next 70 years. The serious land use omissions identified in the Strategy are:

* Failure to recognise climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies available for combating the Climate Emergency identified by the IPCC.

* Failure to recognise that rural land use is not solely about managing agricultural production but also about managing ecosystem functions and landscapes which the community wants protected and enhanced.

* That land use for agriculture and life style are not incompatible but are transitory and both roles involve land and water stewardship for future generations.

* An incorrect interpretation of climate change modelling on land use in the shire up to 2070.

* That the shire is well placed up to at least 2070 to continue local food production with low food miles to consumers in Australia’s second largest city. The shire’s importance as a food producer will increase as climate change impacts accelerate and diminish regions in the north of state ability to produce food for Melbourne.

* Failure to understand how pasture, crop, horticulture agronomy is constantly changing to meet the challenges of resilient, environmentally responsible food production in the era of climate change.

* Failure to recognise carbon farming and biodiversity farming as legitimate land uses across the farming and rural conservation zones. And that these pursuits have potential to become income sources in their own rights for participating land owners.

* Failure to implement sufficient buffer zones and restrictions such as service road speed limits between farming and residential/ rural living zones to prevent negative impacts on agriculture, biodiversity and safety.

* Failure to highlight and incentivise a culture amongst all rural land owners regarding their responsibilities towards land, water, biodiversity and climate change mitigation stewardship.

* Failure to point out that land, water, and environment neglect is not a legitimate land use.

* Today’s decision makers on the Council cannot forecast the extent of factors associated with climate, human population growth (in Victoria and the world), energy availability, biodiversity, natural assets, disease epidemics, and human well-being that will come into play over the next century to change the balance of competing land uses across the shire’s rural and conservation zones. Once land is lost to rural use through housing and rural living sub-division, it is unlikely to be returned. Their decisions on land use will have impacts for generations to come.

* Community attitudes and expectations for rural land use are shifting from owners with a personal rights focus to owners who are empathetic custodians for future generations so that outcomes for nature, climate change, food production and landscape amenity are enhanced and protected while implementing actions to counter climate change.

In the Farming Zone

Figure: The farming zone embraces 85,000 hectares. Source: MRSC

48% of land owners earn income from agriculture. Of these 72% turned over less than $50,000 per year.

The predominant agricultural land use is livestock grazing for cattle and sheep production and a comparatively smaller area of land is used for production of broad acre crops, hay making and viticulture.

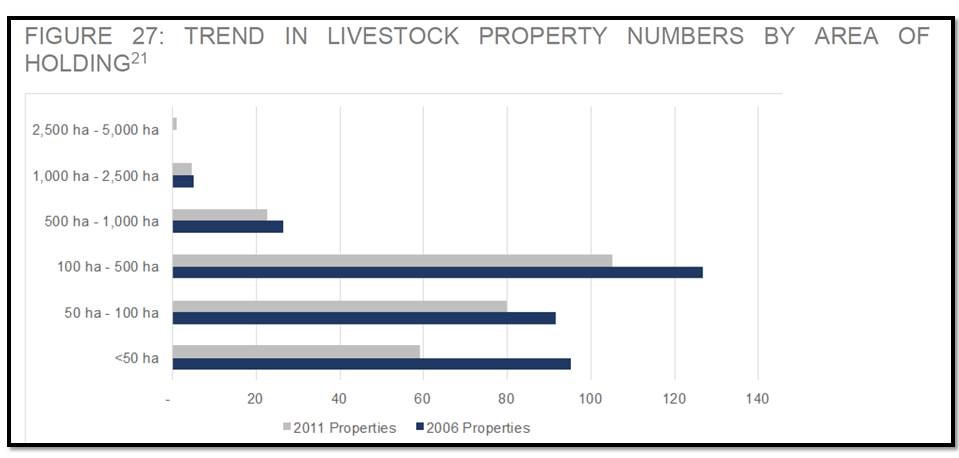

Around 400 farm businesses in Macedon Ranges were reported in the Australian Bureau of Statistics agricultural census, down from 470 in 2006.

Most farms are less than 100ha

Figure: In the farming zone livestock property numbers are declining particularly smaller properties. Source: MRSC

In the Rural Conservation Zone:

Figure: The Rural Conservation Zone embraces 47,000 hectares. Source: MRSC.

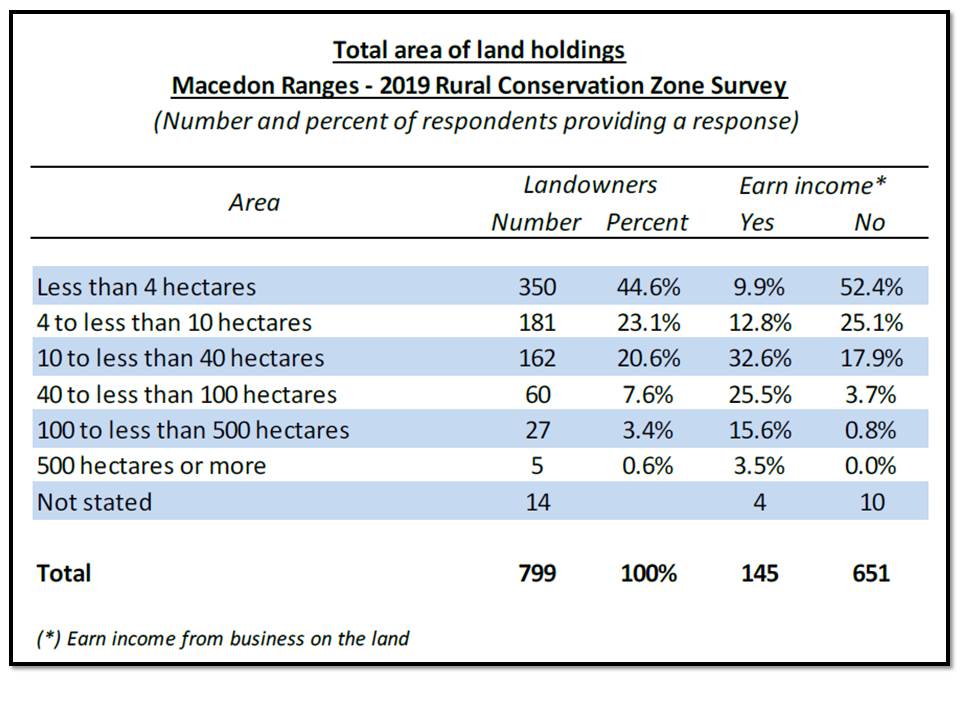

20% of landholders earn income from the land, primarily from agriculture

67% of landholders own less than 10ha

Figure: In the conservation zone few owners earn income from agriculture. Source: MRSC.

Climate change

The Macedon Ranges Shire Council has declared a climate emergency and rural land use is impacted in a range of different ways. However, the impacts for land use are likely to be less than in other regions of the state. The Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) in its “Protecting strategic agricultural land in Melbourne’s peri-urban area” 2019 discussion paper states:

“Climate change is raising average temperatures in Victoria and reducing overall winter and spring rainfall. Areas south of the Great Dividing Range, including green wedge and peri-urban areas, are forecast to experience less impacts from climate change than northern and western Victoria[1]. Farms in this region also have potential access to recycled water from treatment plants, which has the potential to make them relatively drought resistant. As farming becomes harder in other parts of Victoria, we will rely more on agricultural land in green wedge and peri-urban areas to grow food.”

Figure: Average annual precipitation across Melbourne’s peri urban zone comparing historical rainfall to what is anticipated under climate change for 2030, 2050 and 2070. Given the worst case climate change scenario predicted by IPCC, most of the Macedon Ranges Shire can anticipate average annual rainfall above 600mm by 2070. Source: Deakin University’s Land Suitability Assessment in Melbourne’s Green Wedge and Peri-Urban Areas study in 2018

(Note:Future climate projections were developed through the use of the CSIRO ACCESS 1.0 Global Climate Change Model (GCM). This was run through the emissions scenarios or Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP), 8.5 for the years 2030, 2050 and 2070. RCP8.5 is a scenario in which global temperatures reach on average, temperatures that are 4C warmer than pre-industrial averages by 2100. It is the highest representative concentration pathway as described by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. )

Figure: Perennial ryegrass land suitability in Macedon Ranges comparing historical situation to 2070. This pasture indicator species reflects rainfall amount and seasonal duration will support a wide range of land uses in the farming and rural living zones. Source: Deakin University’s Land Suitability Assessment in Melbourne’s Green Wedge and Peri-Urban Areas study in 2018.

Local food production

The Deakin University Melbourne peri-urban land suitability study contends that urban sprawl and its impact on agriculture and food production is an issue all over the world and has been the subject of much research.

“Jan Brueckner (University of Illinois) argued that urban spatial expansion is the result of a growing population, rising incomes and declining transport costs, and therefore urban sprawl is simply the market deciding that land is more valuable for urban uses than it is for other uses such as agriculture. The situation can potentially be reversed if agriculture becomes a more valuable land use.”

Brueckner’s model has been operating in Macedon Ranges shire in recent years. Melbourne’s population has grown, incomes have risen and transport costs have declined. Covid has added a new dimension to the model with more people working from home and ‘escaping’ Melbourne and its potential for lock-down. Together with plentiful land the market has decided that peri-urban Melbourne’s land is more valuable for lifestyle rather than agriculture.

The study identified the geographical areas projected to have the most suitable biophysical conditions (e.g. soil, water, landscape, climate) and greatest versatility into a climate-changed future. The Macedon Ranges shire areas identified are:

* Parts of the Central Highlands region, including Daylesford and surrounds, through to Tylden/Woodend and Kyneton in the north;

* Gisborne and areas north bounded by Kilmore and Tooborac.

These locations generally encompass areas of high suitability (80% and higher) for more than one food commodity when considering the twelve commodities assessed in the study.

Figure: Current and projected climate change impacts for Victoria under high emissions. Source: Primary Production Climate Change Adaptation Action Plan 20221 – 2026

The state government’s “Primary Production Climate Change Adaptation Action Plan 20221 – 2026 highlights how climate change has cross-system risks which impact all rural landowners irrespective of being a business or rural lifestyle.

The stand out climate change mitigation opportunity and new land use across Macedon Ranges Shire farming and rural living zones is carbon farming. That involves sequestration of CO2 from the atmosphere into plants such as agroforests or conservation plantings, and into soil. Carbon Farming is closely associated with another emerging new land use relevant to the shire, biodiversity farming. Both have commercial potential as society and businesses increasingly value land owners whose management contributes to improving ecosystem functions for the benefit of future generations.

Farming zone review

In June 2020 the Shire released a Farming Zone Review undertaken by RMCG. This review identified many issues raised by land owners. The review has been used as the basis for the Rural Land Use Strategy.

But many issues associated with farming and lifestyle neighbours are unresolved:

* failing to control pest weeds and animals and destroy/remove harbor for rabbit warrens and fox dens

* inappropriate buildings from a landscape perspective plus excessive litter such as inoperable vehicles and machinery, structural materials like corrugated iron

* failing to negotiate over mutual obligations for stock proof boundary fences and livestock biosecurity

* inappropriate vehicle use such as dirt bikes without mufflers, often unregistered, using local minor roads and isolated public land for recreation. As well light plane airfields in the farming zone have impacts on the environment (greenhouse emissions, noise) and biodiversity (birds of prey).

Figure: Irrespective of rural land zoning and use, the Shire has failed to ensure all owners manage land appropriately to improve ecosystem functions and not neglect their responsibilities associated with declared weeds such as gorse, blackberries, Montpellier broom and pest animals such as foxes, rabbits and feral cats. Photo: Patrick Francis.

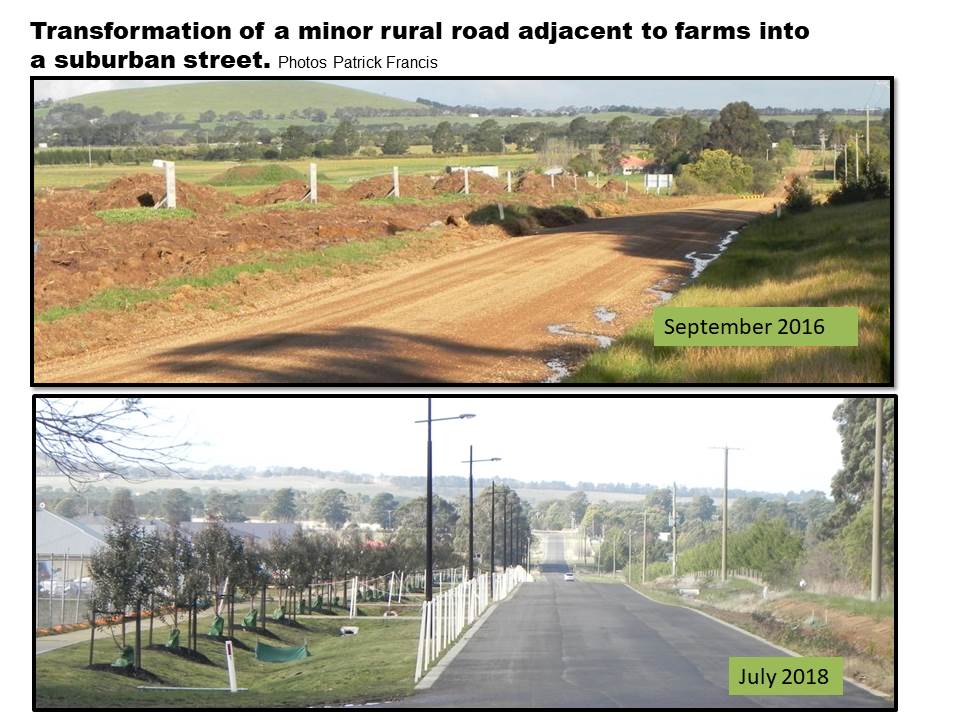

“A buffer between farms and houses is important. Education of new residents to understand what it means for a resident to live in a rural area to manage expectations.”

This failed to happen in at least one residential development, Romsey’s Lomandra Estate. Its southern boundary along Knox road is a Farming Zone. There is no buffer between the houses and the farming land apart from Knox road. This leads to potential conflict with urban residents over dogs wandering on farm land and amongst vulnerable livestock particularly lambs; farmer’s fox control using shooting and 1080 baits both of concern about safety of people and pet dogs; farmer’s herbicide spraying concern over safety for humans and garden; litter blowing into farm land; unsafe vehicle speed on adjacent roads being used for shortcuts into the estate – these roads still have a default 100km/hr maximum speed limit which is inappropriate for the safety of humans walking and riding bikes and horses, and wildlife that has been encouraged to return to farm land through landowners participating in Land for Wildlife and landcare revegetation projects.

Figure: Lomandra estate Romsey has no effective buffer zone between it and the farming zone on the southern side of Knox road. Wildlife from the farming zone are regularly killed and injured due to increased traffic using connecting farming zone minor service roads with a default 100km/hr speed limit to access the estate. Road kills reflect how new residents are unfamiliar with nature and are yet to develop empathy around their driving behaviour towards wildlife and livestock. Photo: Patrick Francis

Figure: Use of rural land in the farming and rural conservation zones can be multi-functional. Moffitts Farm west of Romsey is managed for: wildlife and plant biodiversity improvement; water quality; local low food miles quality red meat; soil health and soil organic carbon; climate resilient pastures for lower ruminant methane emissions, and carbon farming with timber and conservation forestry to be a net greenhouse gas sink. Photos Patrick Francis.

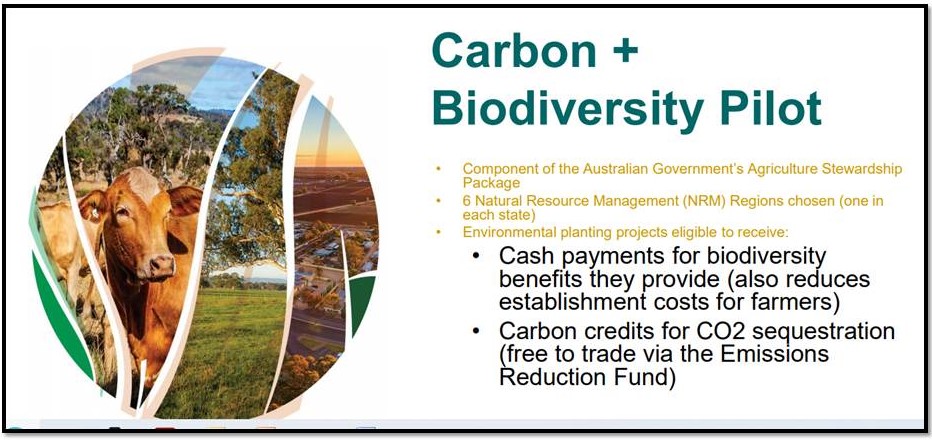

The change in approach from farming for productivity to achieving holistic outcomes in association with food and fibre production is demonstrated in the federal government’s 2021 Agriculture Biodiversity Stewardship Package.

The Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment stated that the package will “…reward farmers for protecting biodiversity and identify other sustainability opportunities. Environmental markets and certification systems can reward farmers for protecting and improving biodiversity. They can diversify and boost farm income, providing alternative income sources to build resilience”.

Figure: A new era in rural land use is emerging where income from outputs other than food and fibre will become common as governments and businesses seek to offset greenhouse gas emissions and raise their status as responsible corporate identities that care for nature and biodiversity. Source: Professor David Lindenmayer, National Landcare Conference August 2021.

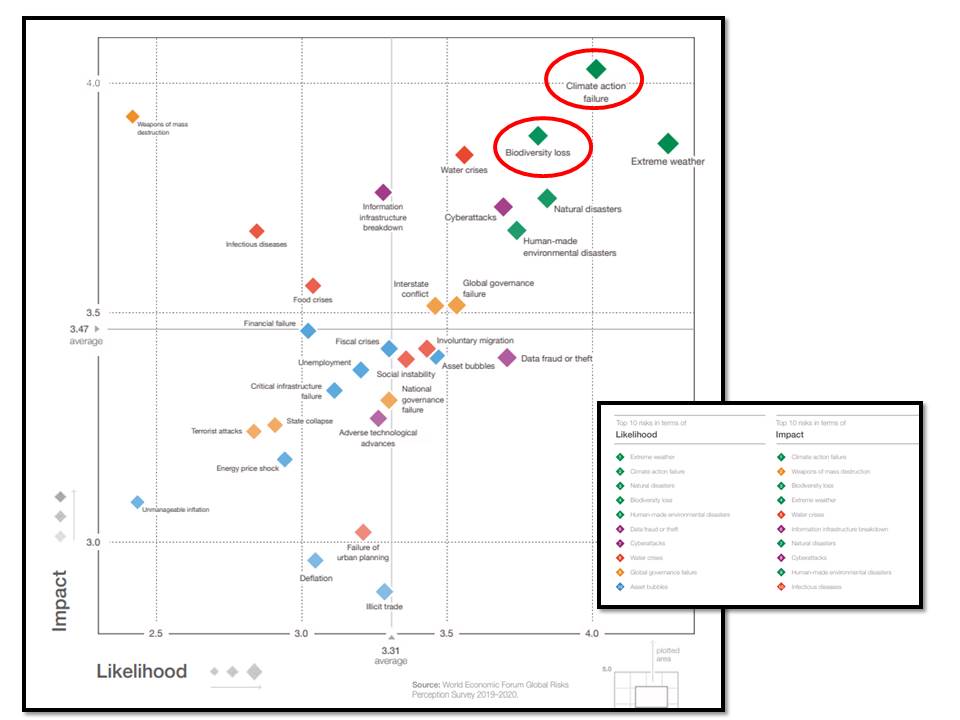

How serious biodiversity protection and enhancement is becoming to businesses is demonstrated by The World Economic Forum’s “The Global Risks Report 2020”. In the chapter on the importance of protecting and enhancing biodiversity it states “Biodiversity and nature’s contribution to people….are the bedrock of our food, clean water and energy… Biodiversity loss has also come to threaten the foundations of our economy.”

Figure: Biodiversity loss is now considered by business as a significant and likely risk, not far behind climate change. Source: The Global Risks Report, World Economic Forum 2020.

Figure: Previous farming reviews for the Shire have taken a ‘silo’ perspective to agricultural metrics concentrating on farm size and income. Future strategies need to take a combined metrics approach where a combination of factors are considered such as land and water ecosystem functions stewardship, climate change abatement, biodiversity, food productivity, animal welfare and farm greenhouse gas balance in evaluating rural land management and direction. Source: Macedon Ranges Farming Zone Review 2020.

Lower emissions and carbon farming

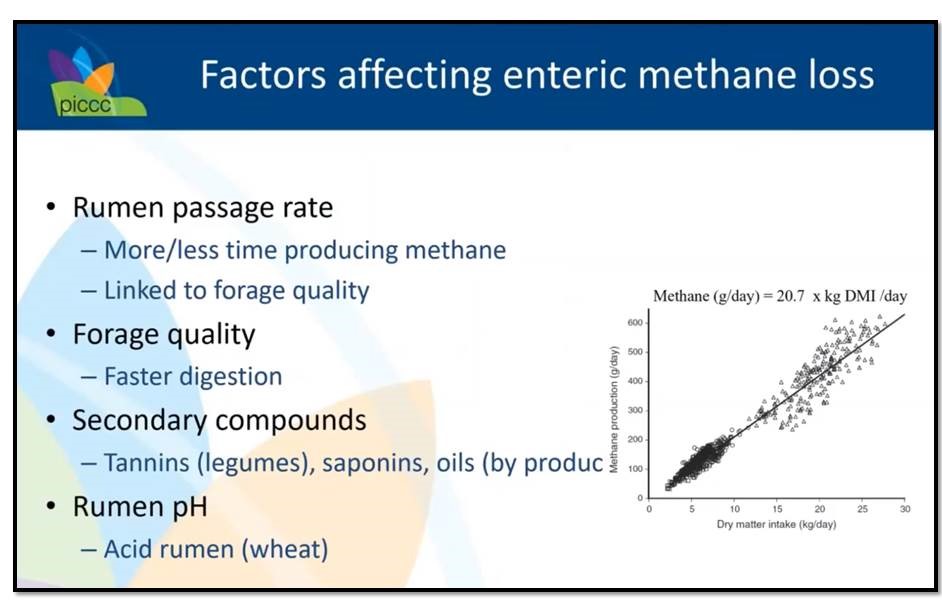

Best practice farming has been moving over the last 30 years toward ecological sustainability as well as profitability, high quality food production, and high level of animal welfare. In the last 10 years another two metrics have been added to best practice, these are particularly important in the ruminant livestock sector which predominates in the Macedon Ranges Shire. They are lowering livestock greenhouse gas emissions and carbon farming to sequester CO2. These are not mutually exclusive metrics they work in combination to produce optimum outcomes across the entire farm.

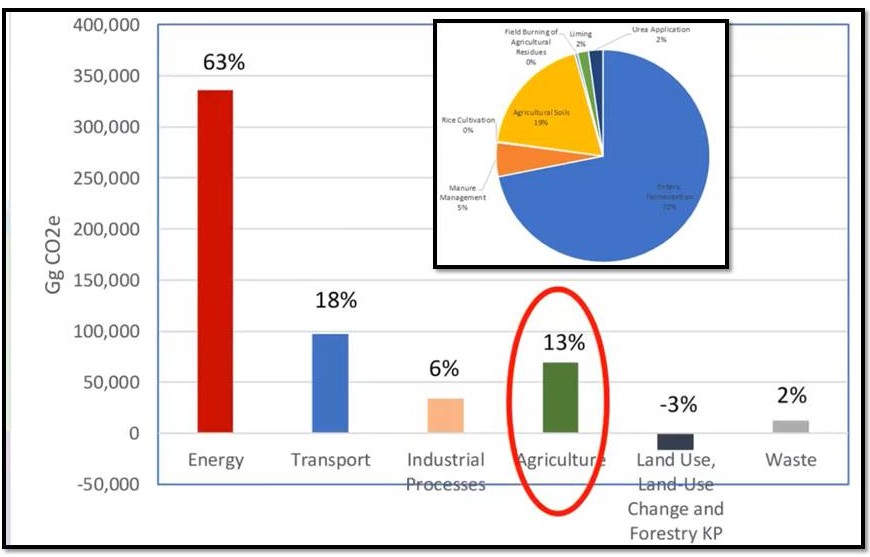

Figure: Australia’s greenhouse gas annual emissions profile shows agriculture is responsible for 13% of the total. The agricultural emissions profile is dominated by enteric methane production from ruminant livestock which accounts for 72% of total emissions (inset). Source: Professor Richard Eckard, University of Melbourne, June 2019 webinar.

Holistic metrics for farm land require a radical broadening of what constitutes agricultural outputs especially in Macedon Ranges Shire where the trend in ownership is away from producing food and fibre in a commercially profitable business towards owning land for lifestyle, with no requirement for agricultural profitability.

It is important to recognise that the current trend in land ownership is likely to be transitory and future generations of land owners may change direction and utilise land of such high soil quality, total annual rainfall and relative rainfall reliability despite climate change, for food and fibre production more than for lifestyle. The key here is that the Shire’s land use planning policy retains as much if not all of the current 135,000 hectares of farming zone and rural conservation zone in its present state and does not allow it to become rural lifestyle and residential land.

Change of rural land use from agriculture to lifestyle should not be a permanent loss of land to future food and fibre production, rather a temporary change. Its return to agriculture if needed will require different management and the vegetation profile adjusted but the land is still available for the purpose.

In the meantime rural lifestyle use of agricultural land presents the shire with an opportunity to assist in meeting the local and Australia’s objectives such as the ruminant meat industries carbon neutral status by 2030 and the state’s net zero emissions by 2050. The Macedon Ranges Shire Council has a policy for zero net emissions from its own operations by 2030, but seems to have no emissions objectives for its farming, conservation, rural living and residential zones.

Its farming zone and rural conservation zone have enormous potential to become a major greenhouse gas sink while protecting and enhancing the region’s biodiversity, opportunities enhanced by the current trend from agriculture production to rural lifestyle. The federal government’s 2021 Agriculture Biodiversity Stewardship Package reflects the progress being made in this direction.

That’s because the greatest opportunity for greenhouse gas sequestration, particularly CO2, comes from abatement be it protecting and enhancing remnant vegetation or revegetation of previously cleared or naturally treeless land. Farming Zone areas 1, 2 and 3, and Rural Conservation Zone precincts 1, 2, and 3 have enormous scope for both these abatement processes in conjunction with agriculture or with lifestyle land use.

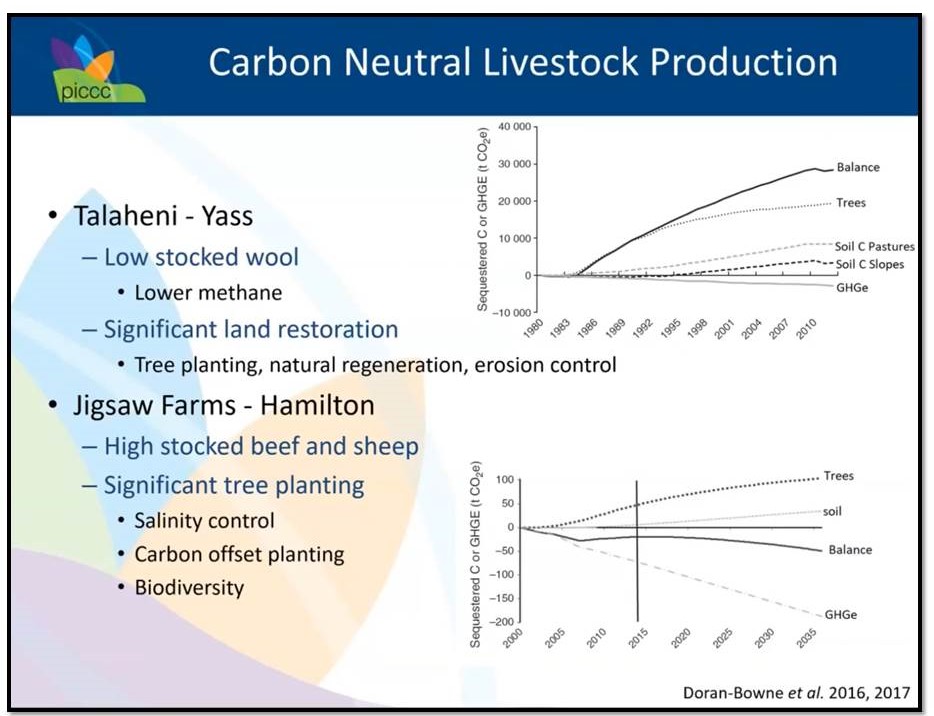

Two University of Melbourne farm case studies with high and low productivity objectives highlight the importance of holistic thinking and management to achieve multiple outcomes for ecosystem functions, for greenhouse gas abatement and food and fibre production.

Figure: Carbon neutral livestock production is possible for large and small farms and even lifestyle farms when holistic thinking is implemented. In this University of Melbourne study the major impact on each farm’s carbon sequestration balance was tree planting. It also positively impacted other ecosystem functions. Source: Professor Richard Eckard, University of Melbourne, webinar June 2019.

The critical point is that while lifestyle land ownership is not supporting commercial agriculture, providing it is retained under existing policy settings which prevent further subdivision in both zones, it can act as an ecosystem functions “caretaker” until circumstances change and more high quality farming land is required for local, low food miles, low emissions food and fibre production. It is not difficult to convert low productivity perennial pastures into high productivity, low emissions for production via livestock or cropping or horticulture.

Figure: Lifestyle ownership in its current policy settings in the Farming and Rural Conservation zones can be an effective method for ‘caretaking’ farm land while its use for food and fibre production is not required. Left, bent grass dominated pasture with a livestock carrying capacity of around 4 – 6dse/ha and high livestock emission per kg of live weight gain. Right: Multi-species perennial pasture with legumes, herbs and grasses with a year round livestock carrying capacity of 14 – 16 dse/ha and low livestock methane emissions per kg of live weight gain. Conversion is not difficult but requires knowledge of pasture species, grazing management, and understanding of sources of farm greenhouse gas emissions. Photos: Patrick Francis.

Figure: Existing bent grass dominant pastures in the Shire are low quality requiring high dry matter intake per kg of live weight gain and slow digestion, both adding to enteric emissions. In contrast high quality pastures have high nutrient density resulting in lower dietary intake per kg of live weight gain and faster digestion, both lowering emissions. Source: Professor Richard Eckard, University of Melbourne, webinar October 2019.

Figure: Lambs grazing lucerne chicory pasture in February. Not only does this pasture mix allow for minimum greenhouse gas emissions it also acts as a fire refuge. Compare the grass dominant pasture in the adjacent paddock with its dry fuel load. Photo: Patrick Francis.

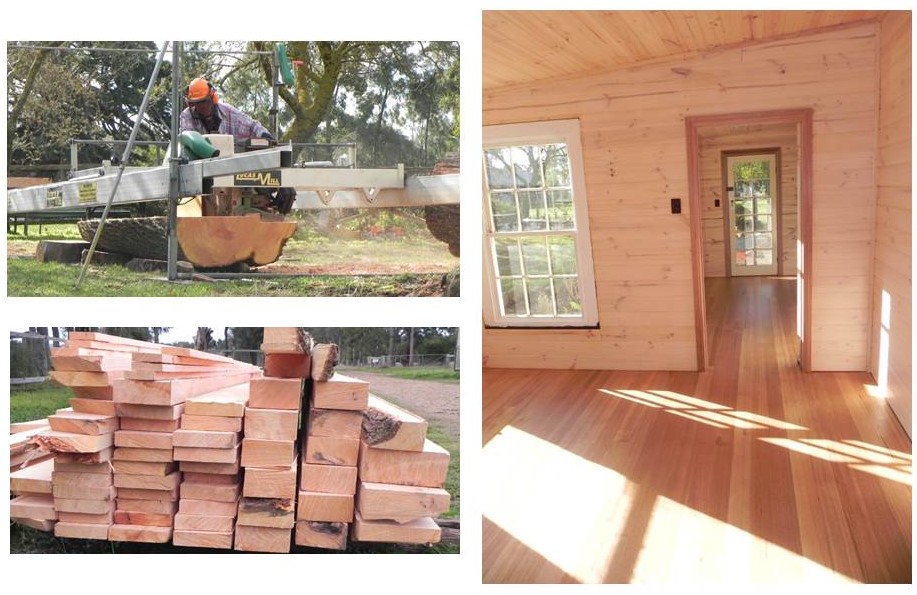

Carbon farming with tree planting

Farm forestry or tree planting policy for the shire is another important omission in the Farming Zone Review when it comes to embracing a wider definition of agriculture and for tackling climate change and achieving net zero emissions by 2030. Tree planting is the most practical method for landowners to be involved in carbon farming and it applies equally across the farming zone and farm conservation zone. The sort of tree planting that should be encouraged across the shire’s 135,000ha of rural land can be described as small scale high value forestry or boutique forestry.

Alternatively, forestry can be conservation orientated to increase biodiversity and water quality with no harvesting. The difference between agro-forestry planting and conservation planting is the former involves silviculture to manage tree form and growth and fire prevention, while the latter involves no particular management and minimal fire prevention strategy.

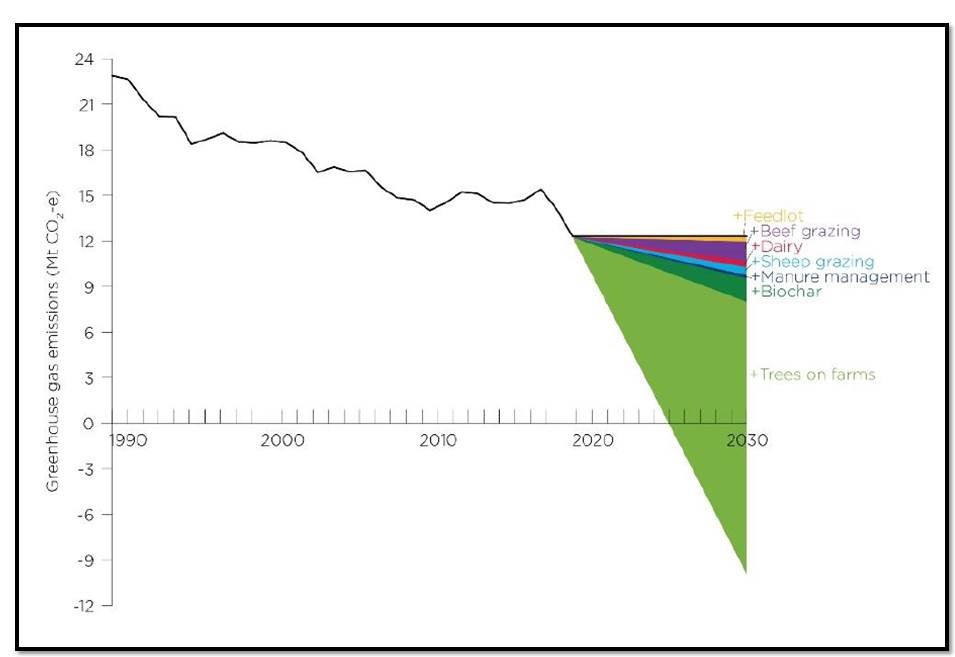

University of Melbourne farm case study analyses have shown that farm forestry for timber or conservation purposes can sequester sufficient CO2 to achieve carbon neutral or carbon sink status for a farm irrespective of agricultural enterprises involved. Low agricultural output farms and lifestyle farms which are increasing in the shire have enormous potential to become net carbon sinks through tree planting for forestry and/or conservation.

Figure: Long-term NSW emissions from enteric methane (black line). Predicted relative contribution of livestock emissions reduction and sequestration options. Livestock emissions reductions estimates are at 2030 and sequestration with trees on farms are cumulative changes from 2020 to 2030. Source: Cathy Waters Charles Sturt University Graham Centre conference, July 2021.

Cathy Waters NSW DPI pointS out that carbon farming under the Federal Governments Emissions Reduction fund has seen extensive changes in land-use across Australia.

“Many land managers in western NSW and an increasing number of farmers in higher rainfall areas are entering carbon markets. The sale of Australian Carbon Credits (ACCUs) through the Federal Government’s Emissions Reduction Fund has helped … increase revenue streams and diversify incomes.”

She said farmers don’t have to involve themselves in carbon markets to benefit from tree planting’s environmental benefits. Food products produced in conjunction with carbon farming provides potential market advantages through the production of premium priced products, environmental labelling e.g. Carbon Neutral Certification, or provenance labelling.

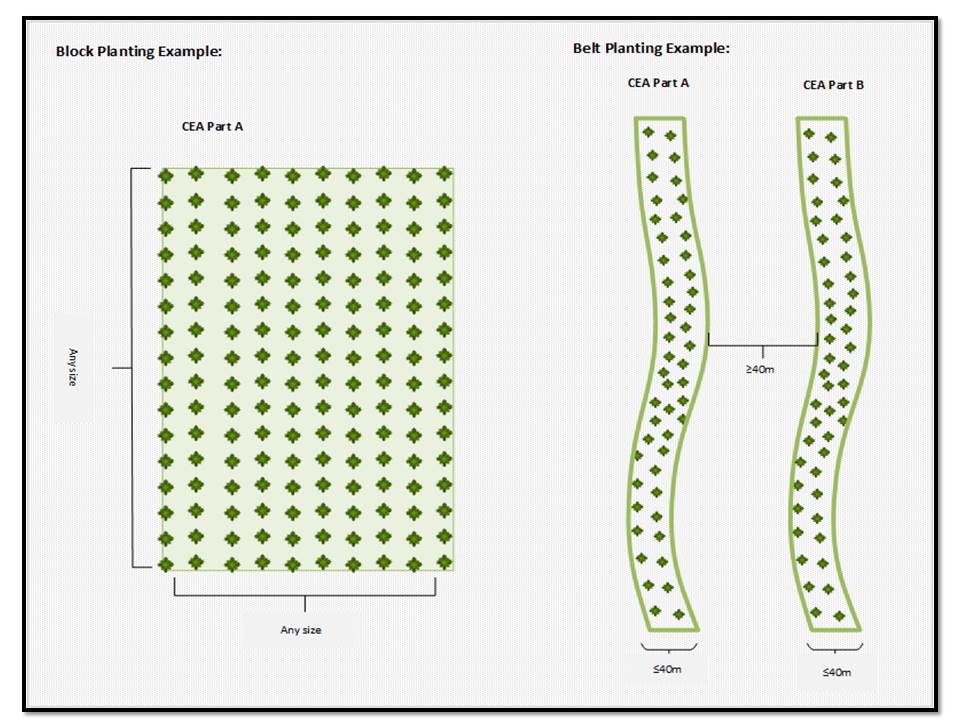

A new initiative to financially support small landholders participation in carbon farming was announced by the Australian Government’s Clean Energy Regulator in early September 2021. It is relevant to Macedon Ranges shire farming and conservation zones as it is encouraging environmental plantings under 200ha in blocks and belts. It opens the potential for small landholders to amalgamate plantings with the support of a carbon broker and generate income through the Emissions Reduction Fund.

Figure: In the ERF new environmental planting pilot for small landholders block plantings can be in many different configurations including being planted in strips or alleys to follow fences or ridge lines to provide shelter to stock – the “belt” restrictions in the model apply more to how far apart the trees are planted from each other than the actual shape they are planted in. Source: Clean Energy Regulator, Streamlining the Emissions Reduction Fund – Environmental Plantings Pilot.

Figure: Two examples of carbon farming in the Macedon Ranges Shire farm zone. Left: Silviculture managed wood lot, pruned and thinned for high value timber products. Right: Riparian zone protection with conservation species planted both sides of creek plus additional forestry species planted on right side. These farms are making an important contribution to climate change abatement and biodiversity enhancement with and without traditional farming enterprises. Photos: Patrick Francis.

Landowners in the farm and conservation zones should be encouraged and even incentivised to plant up to 25% of their land area to trees for boutique agro-forestry or conservation or a combination of both. On properties with remnant vegetation already occupying 25% of the land area further tree planting may be inappropriate from a landscape and biodiversity balance and fire risk perspective.

Figure: Three carbon farming case studies in the Shire’s farming zone areas 2 and 3 are already net greenhouse gas sinks as a result of tree planting over the last 20 years for conservation, agro-forestry, riparian zone protection and landscape amenity. The vast majority of the landowners in the shire whether farming or lifestyle are yet to grasp the opportunities around carbon farming (inset bottom right).

Figure: The importance of growing trees for timber and conservation to combat climate change is illustrated by University of Melbourne forester, Rowan Reid, with an analysis of the amount of CO2e in a 10cm3 block of wood. Source: National Landcare Conference August 2021.

Figure: Portable saw mills are a game changer for small scale boutique agroforestry. Timber can be cut and dried on farm and used or sold for high value uses such as house floor boards and benches. Structural and furniture grade timber provide long-term carbon sinks, ensure re-planting timber trees for continuous CO2 abatement, and provide local, on-going employment opportunities. Photos: Patrick Francis.

The draft Rural Land Use Strategy

So far Council has been ineffective in capacity building as it lacks the holistic farming knowledge to achieve it amongst the majority of farming zone landholders who practice agriculture on a part-time or lifestyle basis. It has failed to reduce land use conflict by not educating new lifestyle and residential zone land owners about farming, biodiversity and greenhouse gas abatement issues associated with the farming zone. It has also failed to implement programs such as an Environmental Best Management Practice program which puts responsibility of landowners to manage land and water assets and not neglect them.

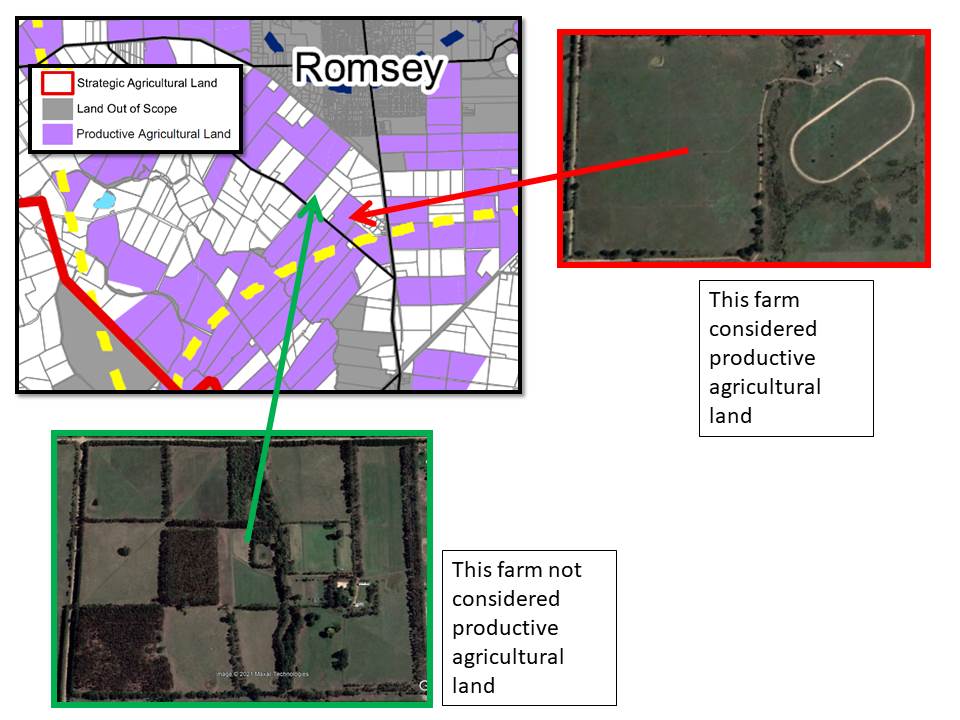

The agriculture objective outlines a difference between land use called “strategic agricultural land” and within it “productive agricultural land”. The basis on which this differentiation is undertaken defies agricultural science, soil science and climate science. The figure shows fence lines dividing farm titles as demarcation between productive and strategic agricultural, this is clearly nonsense because it has no scientific or productivity basis for the distinction. The reference to “productive agricultural land” within strategic agricultural land should be removed. All land can be productive but how productive should be based on scientific assessments.

The fact that the Draft Strategy nominates “strategic agricultural land” and “productive agricultural land” without any reference to climate change abatement highlights its focus is too narrow to assist with the way forward for rural land in the climate change era.

Figure: The demarcation between “productive agricultural land” and other “strategic agricultural land” is completely arbitrary and has no scientific, productivity per hectare, or climate abatement basis.

The Draft Strategy’s objective for Environment Hazards, Landscapes & Catchments recognises that many owners are poor managers of their land as identified in the 2019 and 2020 surveys. Council has not made any recognisable differences to these land owners’ attitudes. This Draft Strategy continues to ignore the situation.

Many landholders have adopted Land for Wildlife conservation programs to support biodiversity increase across the shire but without a reduction of the default 100km per hour speed limit on minor roads, animals will die or be injured. Erecting road signs to warn drivers of wildlife have proven ineffective.

Figure: Despite encouraging wildlife protection and enhancement across farming and rural conservation zones through its Biodiversity Strategy 2018, Council has been ineffective in protecting wildlife from death and injury on minor rural roads which have a VicRoads imposed default 100km per hour maximum speed limit. Signage to alert drivers of wildlife on and adjacent to roads is ineffective with many landowners, town residents and tourists having no empathy with wildlife and understanding that at speed above 50km per hour it is virtually impossible to prevent a collision or run-over. Photos: Patrick Francis.

This objective makes reference to rural farmed landscapes “…as an important feature .. across the shire.” However there is no recognition for important landscape restoration which has taken place in parts of the farming zone where remnant vegetation has been removed over the last 150 years. Revegetation in a range of forms such as conservation plantings and agro-forestry is an important component of rural land use but is not promoted apart from protecting remnant vegetation. In farming zone area 3 remnant vegetation is extremely rare.

Figure: On most farming zone properties especially in area 3, remnant native vegetation is rare with most trees being pines and cypress hedges planted over the last 100 years. Some landowners have made multiple ecosystem functions improvements through revegetation for conservation and small scale agroforestry. Photos show Moffitts Farm, Romsey in 1986 and 2020.

Figure: Two contrasting approaches to land management during a dry summer/autumn, March 2009, in the shire. Top: livestock stocking rate exceeded paddock carrying capacity for months and all surface cover has been removed so wind erosion is extreme and potential for thunderstorm soil water erosion is high. Bottom: Same day in March 2009 on a farm where paddock livestock stocking rate has been matched to paddock carrying capacity over summer and autumn ensuring ecosystem functions are protected and livestock welfare maintained. This pasture contains around 2000 kg pasture dry matter per hectare. Photos: Patrick Francis.

Figure: Sandy creek photo point 100 metres from Moffats lane tile drains. Left: clear water flowing on 9 July 2021. Right: Turbid water flowing on 15 July 2021 after 10mm rain caused runoff from Moffats lane into the creek. Excessive Council road maintenance and 100km/hr default speed limit on Moffats lane combine to disturb the gravel surface and contribute to colloid runoff. Photos: Patrick Francis.

The Rural Land Use strategy action suggestion for best practice land management fails to understand that good land management provides its own ecosystem function and land productivity rewards. For instance ensuring livestock paddock stocking rate does not exceed paddock carrying capacity means pastures will be climate resilient, rainfall infiltration will be improved enhancing pasture growth, and the soil food web will remain vibrant irrespective of rainfall and contributing nutrients for pasture growth. Planting trees for conservation and agroforestry improves across farm landscape amenity, provides shade, shelter and food sources for livestock, bees and wildlife. These are often referred to as co-benefits best practice land management.

Key word search

The lack of understanding between zone policy and rural land use is reflected in a key word search in the Strategy for food production, climate change and environment, table 1.

Table 1: Incidence of key words in the Draft Rural Land Use Strategy 2021

| FOOD PRODUCTION | # 1 | CLIMATE CHANGE | # 14 | ENVIRONMENT | # 149 |

| Soil cover | 0 | Emissions Reduction Fund | 0 | Land for Wildlife | 0 |

| Food miles | 0 | Australian Carbon Credit Unit | 0 | Biodiversity credits | 0 |

| Quality assurance | 0 | Fossil fuel | 0 | Weed | 7 |

| Soil carbon | 0 | 1.5C warming | 0 | Agroforestry | 0 |

| Soil food web | 0 | Net zero emissions | 0 | Land stewardship | 0 |

| Soil biology | 0 | Ruminant emissions | 0 | Road kill | 0 |

| Soil nutrients | 0 | Methane | 0 | Vehicle speed | 0 |

| Soil | 3 | Nitrous oxide | 0 | Rabbits | 1 |

| Soil water holding | 0 | Carbon farming | 0 | Fox | 0 |

| Soil structure | 0 | Climate emergency | 0 | Feral cat | 0 |

| Soil erosion | 0 | Abatement | 0 | Kangaroo | 0 |

| Pasture cover | 0 | Carbon broker | 0 | Pest animal control | 0 |

| Pasture species | 0 | Carbon sequestration | 1 | Environment Best Management Practice | 0 |

| Crop species | 0 | Carbon dioxide | 0 | Stewardship | 0 |

| Agronomy | 0 | IPCC | 0 | Revegetation | 1 |

| Soil nitrogen fixation | 0 | Soil carbon | 0 | Remnant vegetation | 4 |

| Direct drill | 0 | El nino | 0 | Direct seeding | 0 |

| Perennial grasses | 0 | La nina | 0 | Ploughing | 0 |

| Pasture legumes | 0 | Indian ocean dipole | 0 | Tree | 0 |

| Soil pH | 0 | Drought | 0 | Shrub | 0 |

| Stocking rate | 0 | Fire | 49 | Native grass | 3 |

| Carrying capacity | 0 | Ecosystem functions | 0 | ||

| Livestock welfare | 0 | Algal blooms | 0 | ||

| Climate resilience | 0 | Natural assets | 1 | ||

| Property water supply | 0 | Dam water quality | 0 | ||

| Landscape amenity | 1 | Mental health | 0 | ||

| Biodiversity loss | 0 |

This table reflects how far away the Draft is from a land use strategy. The fact that food production is only mentioned once for a shire with around 135,000 hectares of rural land highlights the strategy’s concentration on contemporary use rather than future opportunities. Even when the environment is mentioned 149 times there are no details about what land uses are involved to enhance the Shire’s environment.

Climate change abatement initiatives are neglected nearly as much as food production with only 13 mentions with the major interest in this regard being fire protection. While fire minimisation and protection of assets are important the causes of increased fire risk must also be addressed with IPCC world consensus that climate warming must be restricted to 1.5C by 2050. Rural land owners have a particularly important role to play in meeting this objective by implementing land use strategies that contribute to greenhouse gas abatement. Rural land ownership should be associated with levels of climate change action which are incentivised through land rates.

Conclusion

The draft Rural Land Use Strategy stated at the start that it “….will need to provide a framework to:

Prioritise and balance rural land use aspirations.

Respond to local circumstances and communities.

Clarify the land use and development opportunities for rural land.”

It has failed to achieve these three objectives.

Update:

On 14 December 2022 Macedon Ranges Shire Councilors voted to end the Rural Land Use Strategy Project and consider it again sometime in the future. The Council realised from all the submissions from local farmers and landowners that the draft Strategy was inadequate and needs more thought put into it.

Patrick Francis is a farmer producing prime lambs, processed in Kyneton for the Melbourne market. His family has owned Moffittss Farm since 19523and he purchased it from his father in 1986. The farm has 23% of the land area devoted to environmental plantings and agroforestry trees and is a net greenhouse gas sink to the tune of 250 tonnes CO2 equivalent per year.

Many thanks Patrick for such a lucid, detailed and well-researched commentary on the Macedon Ranges Land Use document. I live just outside your shire in Denver, near Glenlyon, in Hepburn Shire. I am one of those who have retired to a former livestock farm of 40 acres but with nointention of using the land in that way. Rather, I wish to maintain and if possible increase the viability of the soil and theroughly 60% forest regrowth as a biodiversity area. In the decade I have lived here I have seen a large increase in the number and variety of bird life, particlarly water birds, and a stable regerating population of kangaroos and echidnas. Rabbits were almost never seen when I moved here but are now, along with foxes, are regularly seen close to the house or crossing paddocks in the evnings and mornings. Gorse control/eradication is becoming another serious problem on my block and nearby. As the sole occupant of this block there is only so much I can manage to do and afford, so I welcome your most sensible input into the argument for including land maintainance and biodiversity as important elements in any consideration of local area land-use planning.