36 year wait ends in road kill

By Patrick Francis

I started writing this report on 16 May 2022 with a sense of optimism, after 36 years of natural capital restoration on Moffitts Farm we had achieved some significant wildlife species returns, the latest being wombats. By 19 May 2022 that sense of achievement was dashed with a wombat the victim of road kill on Moffats lane adjacent to our riparian zone where the “new” wombat(s) was living. And the cause excessive vehicle speed on a minor rural gravel road that has a legal maximum speed limit of 100km per hour, the same legal speed as on the Melbourne to Romsey highway.

The constant roadkill events surrounding Moffitts Farm and lack of interest at the state and local government levels to address the major cause, vehicles travelling too fast on roads used by wildlife, makes one question the ethics of restoring natural capital on private land close to towns. Is it reasonable to develop habitat for wildlife in areas where there is high potential for them to killed on local roads?

For 36 years our family and a small number of other nearby landowners have revegetated their farms to provide habitat for native animals, protection for livestock, and improve the overall visual amenity of a grazing landscape that in the mid 1980’s was best described as an environmental wasteland. A co-benefit of the revegetation has been atmospheric CO2 sequestration to combat climate change.

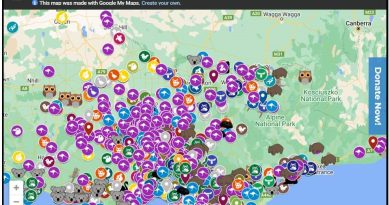

Figure: It’s taken 36 years of investment in natural capital restoration on Moffitts Farm to finally have wombats and other locally extinct wildlife return. But with no support from Macedon Ranges Shire to reduce the legal maximum speed limit on Moffats lane and other nearby minor rural roads, the effort and respect for nature it embraces is in vain. Photo: Patrick Francis 19 May 2022.

But as I took the photos of the bloodied wombat’s body lying beside the road, the question re-emerges in my mind, who cares? Certainly the landholders care, they put an effort into make a difference on their farms, to nurture and support nature over the last 36 years. Do local and state governments and individuals care about wildlife and the impact excessive speed on minor rural roads has on road kills? I suspect they do but there is a missing ingredient without which wildlife road kills will continue unabated.

The missing ingredient for achieving a reduction of wildlife road kills is empathy. Without empathy caring means nothing more than a verbal sentiment. With empathy caring involves action to rectify the situation and minimise if not eliminate wildlife road kills.

Figure: Dash cam images of a wombat crossing Moffats lane on 4 June approximately 30 m from the spot one was killed on 19 May. Fortunately the driver was travelling at 50km per hour and could stop before colliding with the wombat. The time elapsed between seeing the wombat emerge from the east side verge to being virtually under the vehicle was 1 second. If the driver was travelling any faster this wombat would be another road kill. The legal speed limit on the lane is 100km per hour. The road sign at the top of each image illuminated by the vehicle headlights states “wildlife crossing”.

The distinction between caring and empathy is particularly important when it comes to animals because they cannot make the case for their well-being, safety and protection. Humans with empathy for animals do that for them. The wombat roadkill is a perfect example of why caring for wildlife without empathy maintains the road kills status quo and why they will increase as local population growth increases.

The reason why wildlife road kills continue unabated in Macedon Ranges Shire despite constant platitudes around educating drivers about wildlife on roads and the erection of hundreds of warning signs that wildlife are nearby, is simple to explain. None of the Shire’s departments take responsibility for wildlife on minor rural roads. The engineer staff responsible for road maintenance and vehicle speed limits say it not their job to consider wildlife road kills. The environmental staff responsible for road verge and other public land biodiversity say it’s not their job to protect wildlife on roads. Co-operation between these professional groups within the same organisation to change the situation seems to be impossible despite the fact that both know road kills are continuing unabated.

Figure: How two so totally different roads can have the same maximum legal speed limits highlights the lack of empathy for wildlife and inability to co-operate across local and state government departments. Photos: Patrick Francis

So wildlife like the dead wombat on Moffats lane is the victim of bureaucratic silo thinking. Instead of the two departments of Council professionals co-operating to come up with a solution that involves empathy for wildlife they both ignore the cause of the death, vehicle speed, and declare “not my job”.

The silo thinking in local government most likely stems from state government departments who fail wildlife with the “not my job” approach. This is clearly exemplified by the Department of Transport’s who staff base vehicle speed limit decisions on Victorian roads on “Traffic Engineering Manual Volume 3 – Additional Network Standards & Guidelines Speed Zoning Guidelines Edition 1, June 2017”. The words wildlife and road kills do not exist in Manual.

Similarly, the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning’s blue print for native wildlife protection is the “Living with Wildlife Action Plan”. The words road kills or vehicle speed do not exist in the document which the Minister describes as the government’s “…commitment to protecting and conserving the state’s native wildlife…”.

Figure: The lack of co-operation between departments within one organisation like Macedon Ranges Shire is difficult to understand. The Shire recently ran an exhibition in its Kyneton museum to highlight “threats to biodiversity” and the “biodiversity crisis” but could not identify vehicles and speed on local rural roads as a principle cause.

As for the local community who drive on these minor rural roads, it is likely all would say they care for wildlife but for many its without empathy for wildlife. That’s demonstrated by:

* driving at inappropriate legal speed up to 100km per hour, despite numerous signs warning wildlife are present in the verges and adjacent farm land and regularly cross the roads

* equipping vehicles with roo bars to protect them from damage when large wildlife like the wombat are hit.

If drivers had empathy for wildlife they would be content to drive at no more than 50km per hour like many locals do and would not need to equip their vehicles with physical protection devices to avoid any damage when colliding with an animal.

There could be another factor behind local and state governments lack of empathy for wildlife on roads and that is fear of backlash from vehicle drivers who oppose being required to reduce speed. Any politician who advocates for lower speed limits on sections of country roads even if the reason is to save wildlife from becoming road kills is likely to lose at the ballot box.

Ethical dilemma emerging

The lack of interest in taking action to minimise or eliminate wildlife road kills on minor rural in Macedon Ranges Shire and across the state generally raises a question surrounding the ethics of improving natural capital including wildlife biodiversity on public and farm land where the well-being of the wildlife cannot be assured. The kangaroos, koalas, echidnas, wombats, reptiles etc. which returned to Moffitts Farm to take advantage of habitat established on it over the last 36 years and ended up as road kills are in part our responsibility. Maybe we should not have undertaken the habitat restoration, so the wildlife didn’t return and suffer the risk of becoming road kills?

This personal dilemma for land managers in districts like peri-urban Melbourne and in farm zones around towns ear marked for population increase cannot be ignored as society as a whole needs to make a collective decision around its responsibility for wildlife welfare. Ignoring road kills when a solution is available, lower legal speed limits, is unacceptable.

Figure: The lack of empathy for wildlife by local and state government as demonstrated by failure to address maximum legal speed limits on minor rural roads calls into question the ethics of improving Natural Capital on private land adjacent to roads. Photos: Patrick Francis

The story prior to 19 May

During first four months of 2022 we positioned our wildlife camera on the drive way into the farm. Footprints in the soft gravel suggested a never seen before animal on Moffitts Farm was using the driveway as a track. The give-aways were cube like scats, paw prints and rather large digging under gates and fences along the riparian zone. Yes, a wombat was suspected but until we had a photo we were not 100% positive.

Figure: Footprints and scats found in early 2022 suggested wombats had returned to Moffitts Farm for the first time in our living memory. Photos: Patrick Francis

Eventually the culprit was captured on screen, but so were a host of other animals – some wanted but some unwanted.

Figure: The wombat(s) caught on camera in March and May 2022.

The most unexpected and exciting image caught in early May 2022 was a koala. Koalas are becoming rare in the Macedon Ranges but we have recorded visiting individuals every year. They signal their arrival with the deep grunting call, but this time there was no signal before or after this photo being taken.

Figure: A koala taking a walk along Moffitts Farm driveway in February 2022.

We do have the occasional kangaroo and wallaby visit the farm, but their incidence is reduced as a result of a netting fence around the boundary. Eastern Grey kangaroos are present in large numbers on neighbouring farms but we found that with our holistic grazing management program combined with great habitat in fenced off revegetation corridors, forestry blocks and riparian zone, that the farm was being overloaded with kangaroos and subsequently damaging the pastures plants being rested from grazing. This caused soil ground cover to be compromised in dry/drought years, hence the netting fence on the boundary to discourage kangaroos.

Figure: Kangaroo on driveway in January 2022.

Unwanted animals

While we were not surprised by pest animals, foxes, rabbits/hares and cats being caught on camera, the frequency of their photos is disconcerting. Foxes are a major issue in the district because there is virtually no landholder interest in controlling them as they don’t breed sheep, and have little or no comprehension that they are the major predator of small native species like birds, reptiles and frogs.

The cat(s) caught on camera could come from the nearby town, but photographs do not indicate they have collars on. If feral, where they live is unknown.

Foxes and cats may impact the rabbit population as remains are sometimes found, but this positive does not outweigh their overwhelming negative impact on native wildlife.

Figure: Despite having a range of strategies to reduce feral animals on Moffitts Farm they continue to invade from neighbouring areas.