More emphasis on pasture quality and lower methane emissions – Spring update November 2021

By Patrick Francis

Figure: It is important to recognise pasture species can have significant palatability differences which can impact methane emissions, growth rates and reproductive performance.

An important strategy that ruminant livestock farmers in the agricultural zones have to minimise methane emissions is growing pasture species that have higher palatability and nutrient contents which their animals prefer to eat. It is often not appreciated that pasture species and varieties within species have significant inherent and seasonal sheep and cattle palatability differences.

The impacts of high palatability, high digestibility and productivity pastures are multi-faceted, the livestock eat more herbage which digests quicker so they grow faster, release less methane per kilogram of livestock gain, the pasture re-grows more leaf material which absorbs more CO2 from the atmosphere, and they build soil health by supplying more degradable organic matter for an abundant and species diverse soil food web.

Our holistic grazing management program started in 2000 when we shifted from an Angus breeder herd to finishing purchased steer and heifer weaners. It was a simple system and allowed us to easily manage the grass dominant pastures that developed through rotational grazing. Our pastures based on cocksfoot, tall fescue and phalaris species remained productive through the ability to apply high stocking rates (in excess of 100 dry sheep equivalents (DSE) per hectare) to match seasonal carrying capacity. This strategy meant the perennial pasture grass species which are endemic and prolific in this district but are less palatable, bent grass, sweet vernal and Yorkshire fog grass, were kept in check amongst the higher quality introduced grasses as cattle ensured all plants were grazed evenly and flowering could be prevented.

In 2012 we shifted from cattle to a self-replacing Wiltipoll flock which have specific marketing and logistic advantages to purchased cattle. We maintained the same holistic grazing management program which produced similar lower cost, livestock health, and livestock management advantages as cattle. But there was one important difference, the pasture grass species composition began to change in favour of the less palatable grasses and by 2017 a new approach was needed. While the overall paddock annual livestock carrying capacity remained about the same, this would not be the case as the less palatable species increased their percentage in the pasture.

The issue here is sheep seem to be more discerning as to what species they eat and have the ability to pick and choose compared to cattle. As well, the less palatable species are also less productive with a shorter leaf growing season mostly confined to September, October and November, before flowering. And once the flowering stage is reached they stop growing leaf and senesce over summer. In contrast the summer active cocksfoot and tall fescue species continue to grow leaves as long as they are rested from grazing and there is some summer rainfall.

The impact of these pasture changes were most noticeable with lamb finishing growth rates. In our system lambs are weaned in early December and are rotated around worm larvae free pastures until they reach live weights in excess of 44kg.

Our originally improved pastures (sown during the 1990s) which were losing their cocksfoot content were not producing the growth rates we were looking for to ensure relatively fast finishing while minimising methane emissions. Lambs on grass dominant pastures were growing around 90 to 150 grams per day. In contrast lambs grazing brassica paddocks (the first stage of our pasture renovation program) were achieving 200 – 280grams per day.

In 2017 we started experimenting with devoting particular paddocks for finishing lambs to a mix of chicory and plantain with lucerne or perennial clover. These produced average growth rates over 300grams per day. We were making progress.

But when dealing with biological systems unexpected issues developed. The chicory needed grazing management which prevented it from flowering and in mid to late spring this is difficult as it regrows faster than we like to rotate. The plantain was not summer active and its palatability to lambs was questionable. The Winfred brassica we planted was susceptible to aphid attack and in 2019 was severely affected, killing some plants and rendering others unedible. As well, brassica can have a palatability issue for lambs and growth rates can vary enormously between animals. Chicory while a great warm season grower with drought tolerance, is not winter active and has around four months not contributing to the feed bank when pasture supply is at its lowest.

Without chicory dominance the unwanted grass species soon began to return. As well, one species planted for cattle pasture, tall fescue, was unpalatable to sheep, so it also began to thrive (uneaten) and compete with chicory.

The challenge was to find species that were complimentary with chicory during spring summer and autumn but would fill the feed gap left by chicory in winter. We tried a suite of perennial and annual clovers, plus a low rainfall perennial ryegrass.

The four white and red perennial clover species and two sub clover species seem to be the right mix with chicory plus ryegrass adding a perennial grass which will utilise any excess nitrogen in the soil generated by the clovers symbiotic relationship with rhizobia bacteria fixing nitrogen.

Lambs grazing the chicory and multi-species of clover and chicory plus lucerne grew at 404 and 409 grams per day over 10 in January 2021. At this growth rate lambs finishing from 30kg to 45kg are likely to be producing 50% less methane emissions per kg of live weight gain than lambs finishing on grass dominant pasture growing at around half this rate.

Figure: This finishing perennial pasture mix of chicory, five perennial and sub clovers, and ryegrass has potential in our region for year round green pasture production, 100% ground cover, high organic matter recycling into soil via manure and biomass, and significantly reduced lamb greenhouse gas emissions due to the plants high palatability and digestibility in the rumen. Photo: Patrick Francis.

Radical change to cell grazing timing

There are other co-benefits associated with have some special high performance pastures of clovers and perennial ryegrass mixed with chicory. This year we changed our lambing logistics to take advantage of higher quality and digestibility they offer. Instead of drift lambing (shifting ewes with new born lambs from the lambing paddocks into a nursing paddock) and subsequent conventional short duration, high stocking rate grazing, we are long-rotation lactating ewes in multiple paddocks of high quantity (3000kg dry matter per hectare) and quality clover based pastures. We are matching paddock stocking rate to carrying capacity for a three to five week graze, starting the week before lambing is due to start. This is a radical change from the four to seven day graze period at high stocking rates (above 80 dse/ha) associated with traditional cell grazing.

The high quality clover, chicory and ryegrass pasture provide ideal feed for lactating ewes with suckling lambs starting (at approximately three weeks of age) to eat herbage and developing rumen function and microbiome.

The problem with short grazing time cell grazing with lactating ewes running at a stocking rate above 50 dse/ha is that the lambs just learning to eat pasture and develop their rumens are being “out-eaten” by their mothers. In other words the ewes with their enormous lactation appetites are dominating pasture grazing, eating the highest palatability and digestibility species like clovers before the lambs have a chance to sample them. And in a short rotation of four to seven days the lambs are left sampling the less palatable, lower digestibility species or perhaps not grazing at all. So we think they are likely to eat less than their potential intake and subsequently rumen development is hindered.

In contrast, with long rotation cell grazing in high digestibility, high palatability pastures, ewes no longer dominate eating the most desirable species, there is plenty of time available for the lambs to sample and ‘learn’ to eat for the entire grazing period which can be up to five weeks.

Figure: Herbs, clovers, and ryegrass pastures are ideal for ewes helping them maintain body condition while lactating and supporting development of lamb rumens. With long-rotations starting at 3000 or more kilograms of green dry matter per hectare and stocking rate below 50dse/ha ewes don’t compete with lambs as they learn to graze the most palatable species. Photos: Patrick Francis.

There is another advantage with the longer, lower stocking rate, grazing rotation for ewes and lambs which relates to animal behaviour and growth rates. Sheep form social groups and hierarchies which the lambs associate with. I contend lambs ‘adapt’ to paddock layouts such as water points, tree and shade areas, ‘playground’ spots such as rocks and tree trunks, and special soil licking spots. In other words lambs become connected to their paddock and the flock members in it. Quickly rotating between paddocks may limit the connections they make to paddock features and possibly disturb hierarchies? It may impact lamb growth rates. I have no scientific evidence for this, it is based on my observations of lamb behaviour.

To assist lambs develop exhibit their natural behaviour we put ‘playgrounds’ in paddocks which don’t have natural hardware such as logs and trees to play on. Most of our paddocks are surrounded by trees and shrubs in fenced off conservation corridors (which we planted as originally there were no trees across the farm) so the trees and fallen branches are not in the paddocks. Lambs want to play by climbing on rocks, stumps, fallen tree trunks and they become a focus for forming ‘play’ groups especially in afternoons.

Figure: We contend lambs become adapted to the paddock they are born in and need time to know its layout and features including playground areas such as logs (which we put in each paddock). Rotating them between paddocks too frequently may add a level of stress as each time they must familiarise themselves with new pasture species and layouts. Photo: Patrick Francis.

Figure: Lambs probably develop social groups and hierarchies through play. We suspect longer paddock rotations and less animals per paddock help these to be maintained and reduce stress associated with moving and mixing and may improve growth rates. Photo: Julie Francis.

Pasture plans

Our plan is to develop around 30% of the farm’s pastures to chicory, multiple clovers and perennial ryegrass. Summer active chicory and perennial clovers also provide a fire refuge if needed. The remaining paddocks will be continue to be renovated with multiple species perennial summer and winter active dormant grass species plus perennial clovers and sub clovers. These will provide the main source of nutrition for dry ewes post weaning through to pre-lambing and for dry stock replacement ewe hoggets, wethers and rams.

Another pasture management strategy introduced this spring is extensive pasture topping of the undesirable, unpalatable grass species when they flower. Our observation is that where bent grass, sweet vernal and Yorkshire fog form flowers, sheep will not graze amongst the stems even if clovers are underneath. Topping is a low emissions tractor use as it requires lower power than slashing close to the surface and is relatively fast. The stems are slashed green so they quickly decompose into soil organic matter compared to topping dry stems in summer and autumn.

Figure: All our chicory, clovers, ryegrass pastures have approximately 10 – 15% un-renovated grass dominant pasture like this cocksfoot. It is interesting that the sheep will graze this in conjunction with the higher quality chicory and clovers. The key is access to pasture species diversity to help ewes and lambs to optimise intake. Photo: Patrick Francis.

Figure: Once a low palatability pasture species like sweet vernal becomes dominant and begins flowering in September, sheep are reluctant to graze the sub clover amongst it. Photo: Patrick Francis

2021 rainfall

2021 has been an excellent year throughout for rain. Following the above average 2020 rainfall (872mm) the year started with 93mm in January setting up strong summer pasture growth. While February and April were well below average rainfall average falls in March and May kept pasture growing. June rainfall was about twice the average and resulted in water logged soils through winter which continued in low lying areas of paddocks right through to November as spring rain was at or above average.

Water logging is a risk for spring pasture renovation as it can stop sowing at the optimum time in October. This proved to be the case with four paddocks sprayed out for renovation in October but only one was dry enough to direct drill early in the month. A second was sown in early November and two are still waiting to be sown.

Figure: In some pasture water logging has continued for most of winter and into spring. This may have negative implications for cocksfoot species survival. Photo: Patrick Francis

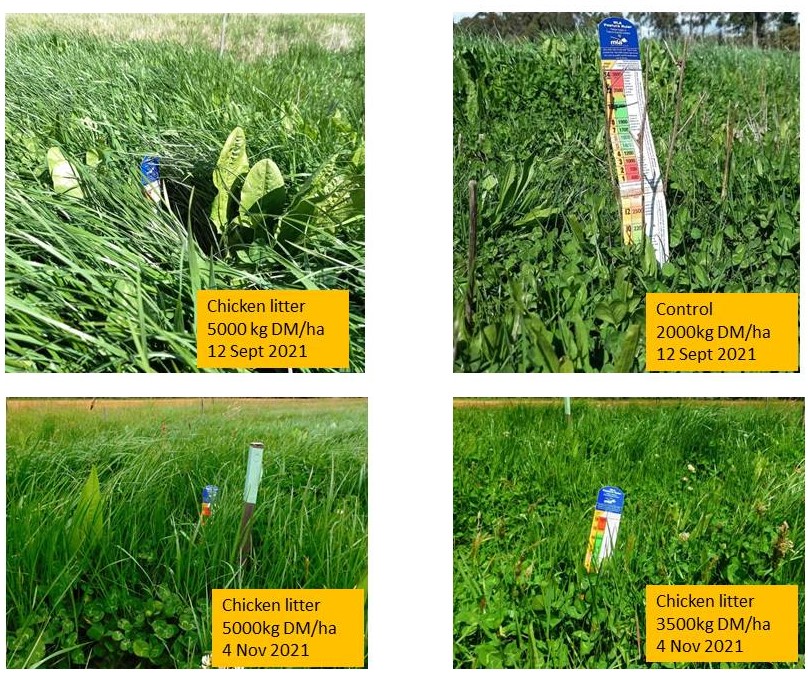

Chicken litter demo

When our poultry shed was cleaned out of three years worth of saw dust and poo I used some of it for a pasture growth demonstration applied in June at the equivalent of up to 12 tonnes per ha on a clover chicory ryegrass pasture (sown 2019) and on brassica regrowth paddock (sown October 2020). The results were beyond belief for the pasture. By early September all the plots had grown and enormous bulk of pasture, sufficient for high quality fodder conservation (not what we do).

The growth impact was greatest on the ryegrass and chicory components of the pasture suggesting a soil nitrogen deficiency, probably exacerbated by water logging conditions. Urea was applied on surrounding pasture on 9 July at 45kg N per ha. The visual impact on pasture growth was minimal and nothing like the impact of chicken litter.

Our lesson from this is to invest in bulk chicken litter applications especially on the chicory, clover, ryegrass pastures. The suite of major and trace nutrients available to plants over up to three years in the chicken litter make it a far more cost effective fertiliser compared to individual nutrient applications of urea, superphosphate and their combinations like DAP. The one negative of bulk litter is it requires a contractor to spread. But even with the spreading cost included, the total nutrient package in litter gives farm more value than spreading the same nutrient load per hectare using individual nutrient fertilisers such as urea, superphosphate and muriate of potash.

Figure: Chicken litter was top-dressed at 4, 8, and 12 tonnes per ha on a chicory, clover ryegrass pasture on 14 June 2021. Despite water logged, cold soil in June and July the pasture grew to 5000kg DM/ha by 12 September when ewes with lambs were put in for three weeks until 3 October. By 4 November the treated plots had regrown to 5000kg DM/ha. Note: the MLA pasture ruler in each photo is a double ruler. Photos: Patrick Francis.

2020/21 Environment update

Staying with pasture renovation, one significant issue in the spring 2020 program was the impact of Australian wood ducks. Two paddocks were direct drill sown with the same chicory, clovers, ryegrass pasture mix on the same day in early November. One was adjacent to a neighbour’s boundary and a dam in a heavily grazed horse paddock, the other was 300m away. The plants germinated successfully but my early January the paddock adjacent to the horse paddock dam that was used by wood ducks was decimated. We thought at the time that the damage was so great the paddock would need to be re-sown. But the damage while looking significant did not have long-term impact. It meant the paddock was not grazed in autumn and winter, but by spring its recovery was nothing short of amazing. Its composition has a little less chicory than the unaffected paddock, but its clovers have compensated for that loss.

Figure: Wood ducks can decimate a newly sown pasture (Top left versus Top right) but in this case the pasture species recovered, probably assisted by average rainfall throughout 2021. Photos: Patrick Francis.

Figure: Australian Wood ducks. Photo: Patrick Francis.

This experience with the wood ducks reminds me that nature works in cycles and that jumping in to artificially ‘solve’ what might seem a serious problem at the time may not be necessary. Given time the problem might actually solve itself. In this case it did, duck grazing subsided and the plants while severely grazed, recovered.

Another good example of nature solving problems happened in a section of direct drill pasture sown in May 2018 where the top soil was shallow due to a layer of basalt rocks close to the surface. The perennial grasses didn’t have access to as much soil moisture as the rest of the paddock and germination in the area was poor. In contrast capeweed germinated and grew prolifically without competition from the grasses. It looked like the capeweed should have been removed with a broadleaf herbicide spray. But in our rotational grazing system we note that capeweed can be highly palatable to ewes when it is fresh and bulky. We never sprayed the capeweed and by spring this year the capeweed has virtually disappeared with the area colonised by perennial grasses and clovers giving 100% ground cover in summer.

Figure: Many perceived problems in pastures such as weeds or pests can be rectified with appropriate grazing management and allowing nature’s cycles time to have an impact. This patch of shallow soil is in a paddock sown in autumn 2019. In spring 2019 this patch was dominated by thick capeweed, but was highly palatable to ewes and was grazed down. In September 2020 the area had less capeweed with perennial grasses more obvious. By October 2021 capeweed plants were hard to find, the space between the expanding perennial grass crowns had been filled with clovers. Photos: Patrick Francis.

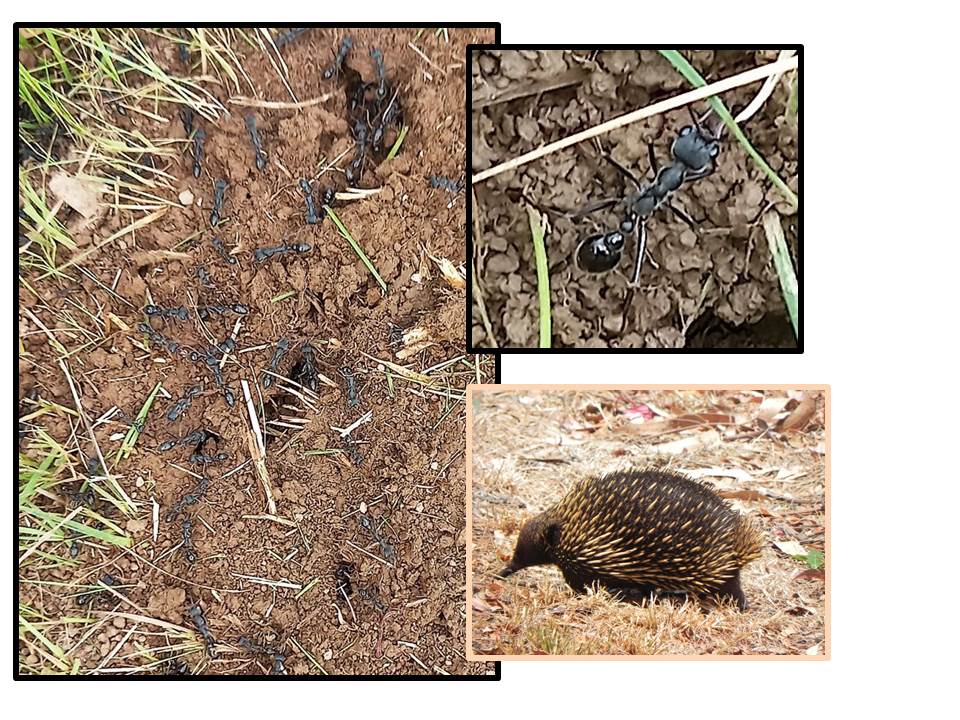

Another emerging biodiversity change is the gradual increase in bull-ant nests across the farm. Bull ants (probably Jack Jumpers) were never seen 10 years ago, now they have nests everywhere, mostly along fence lines and in our agroforests and conservation and riparian belts. There seems to be a relationship between them and trees. Another native animal also increasingly seen is echidnas and this might be because of the increased food supply provided by bull ants. The nests are commonly being broken open and that must be by echidnas.

Figure: Bull ants are becoming increasingly common across the farm, so are echidnas. Are the two related? Photos: Patrick Francis.

Another interesting interaction between native species and the built environment happened again in the farm workshop. Last year a pair of grey shrike thrush reared three young in the workshop in a nest amongst containers of screws and nails. This spring a pair of white browed scrub wren built a nest in a rope coil hanging in the workshop.

Figure: A pair of white browed scrub wrens built their nest in a coil of rope hanging in the workshop. Photos: Patrick Francis

It is fascinating to watch how native birds can adapt to changes in their environment. It is hard to imagine why the scrub wren would build such an elaborate nest in a busy area such as a workshop. It was interesting to see what food the parent scrub wrens were feeding nestlings. Seemed to be insect larvae or caterpillars. This is in contrast to the grey shrike thrush parents who mostly feed small skinks to their young.

Figure: A grey shrike thrush feeds a skink to its nestlings. The nest they are in was built in the workshop the previous year by a Blackbird! Photo: Patrick Francis.

Hi there, i have just stumbled on your article on Pasture Quality and methane emissions.

I found it very interesting and you have a lot of information based on your real time experience which i would like to take advantage off

I have a small hobby farm {3 acres arable} at Ourimbah on the nsw central coast, we currently have 7 wiltipol ewes and 4 wethers.

I have oversown my native pastures with a Italian perennial ryegrass with limited success. I want to try and improve my pastures but am reluctant to use herbicide or cultivate if possible. I was thinking about just broadcasting the seed into the existing pasture and then running some harrows over the ground.

I was wondering if you would mind sharing some information on the seed mix you used that was referred to in the article, while I realise my results will probably be different from yours, I would like to get an idea of a possible direction forward.

I do have a tractor, harrows, chisel plow and a howard 5 ft rotary hoe at my disposal but would prefer not to cultivate if possible.

Im sure any advice you could give me would be a benefit.

Regards Adrian Turner

Hello Adrian,

Glad you found the pasture quality and methane emissions article of interest.

I believe you can change the composition without ploughing but it will take more time and persistence especially as you don’t want to use a knockdown herbicide. My suggestion would be to slash the existing pasture as low as possible prior to your wettest months. After slashing, use the harrows to develop as much surface tilth as possible for a seed bed, then spread a range of perennial clover seeds suitable for your soil type, charateristics and rainfall distribution.

The rotary hoe just skimming the surface could be a better option than multiple passes (more diesel emissions) with the harrows to achieve reasonable tilth for a seed bed. Providing you are don’t till the soil to more than about 2cm it is unlikely you will impact your soil organic carbon level. Even if it is reduced a little it will quickly recover (and possibly increase) via a productive perennial legumes and perennial grasses based pasture which if looked after could persist for decades.

Take a look at this NSW DPI site for some perennial clover and grass varieties as well as sub clovers.

Hawkesbury-Nepean, Hunter and Manning Valleys (nsw.gov.au)

I suggest at least three perennial clover varieties and three sub clover varieties plus at least two perennial grasses. I would not use C4 (winter dormant) grass species in the mix (eg Kikuyu, paspalum, Rhodes grass) as their digestibility over the winter period is low and would encourage higher methane production. I suggest aiming for around 40 to 50% clovers (perennials and annuals) in the pasture year round but the % is likely to vary from year to year depending on distribution of rainfall. It is important to maintain 100% ground cover year round to protect the soil food web (biology) and prevent erosion. Grazing management has to ensure stocking rates don’t exceed paddock carrying capacity for this ground cover percentage to be achieved.

We use chicory in conjunction with clovers as it is a high digestibility, high palatability species, but is relatively short lived, just three years before we direct drill more into the pasture. If you are successful with establishing a persistent clover/grass pasture it will be difficult to oversow by spreading more seed like chicory. But then the clovers and grasses will be doing the job to minimise your farm’s livestock methane emissions.

Hope this helps.

Regards

Patrick