Live exports expansion a threat to on-shore beef processing

Opinion by Patrick Francis

In my March 2015 article on developments taking place in live exports, I wrote about the concern of some industry experts that domestic processing of cattle in Australia could come under threat.

While in March my concern related to possible change taking place in the long-term, reports since then particularly at Beef 2015 seminars in May and the China live export deal in August, suggest the threat is likely to emerge in the medium term, that is within the next five to 10 years.

There is a close analogy between export meat processing in Australia and the demise of the steel processing and car manufacturing sectors. Live cattle are equivalent to iron ore. Both are commodities which are cheaper to shift off-shore for overseas corporations to add-value to and then return to Australian and overseas consumers as finished products.

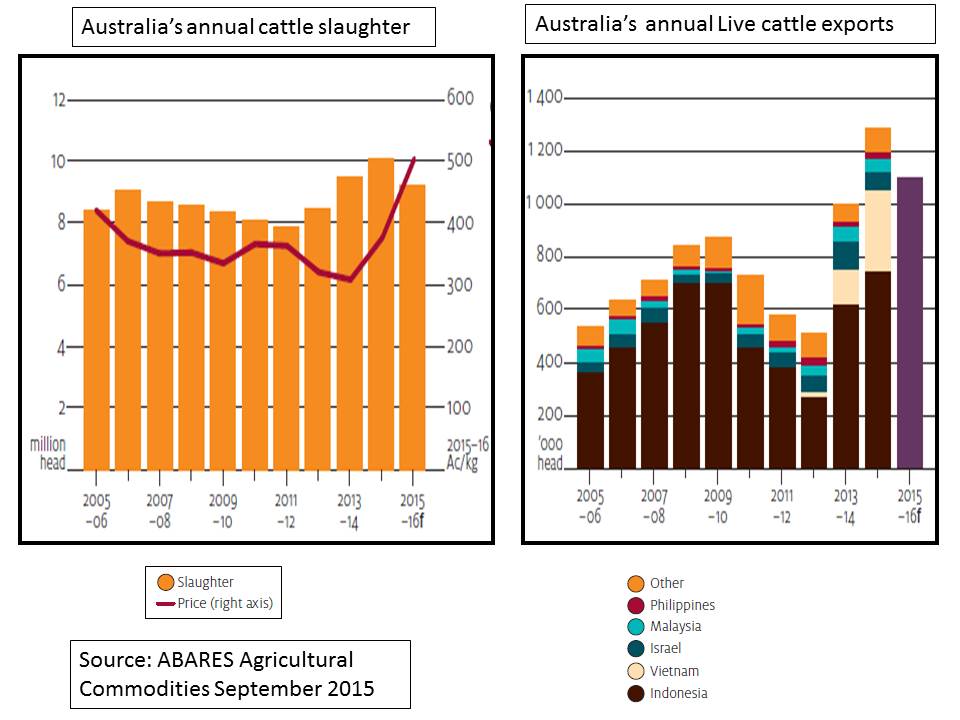

The mathematics behind the impact of a booming live export market on domestic processing is relatively clear when data from the two sectors is compared, figure 1.

Figure 1: Australian cattle abattoirs will have difficulty sourcing enough cattle for cost effective processing in the medium to long term if live cattle exports increase above approximately 1.5 million head annually.

It shows Australia’s annual domestic slaughter is relatively stable (except for periods of serious drought in Queensland where the majority of cattle breeding takes place) and up to 2015 so have live exports been. Domestic slaughter is generally 8 – 9 million head and live exports 600,000 to 1,000,000 head. Most of the live export cattle are sourced from the Top End of Australia, that is across the northern third of Western Australia, Northern Territory and Queensland. It’s an enormous region which supports one export abattoir, and that was built in 2014 by AACo to mainly process its own cattle. Other cattle station owners only have the live export as a market because the cost of transporting young cattle to feedlots in southern WA and south eastern Queensland is prohibitive.

There are suggestions that by 2030 Australia could be exporting 4 million live cattle. If that occurs the domestic processing sector would be left with between 5 and 6 million head to slaughter. That may make processing for export markets in Australia unviable.

The evidence for beef cattle live exports causing a gradual demise in on-shore processing of export cattle comes from five components of the value chain:

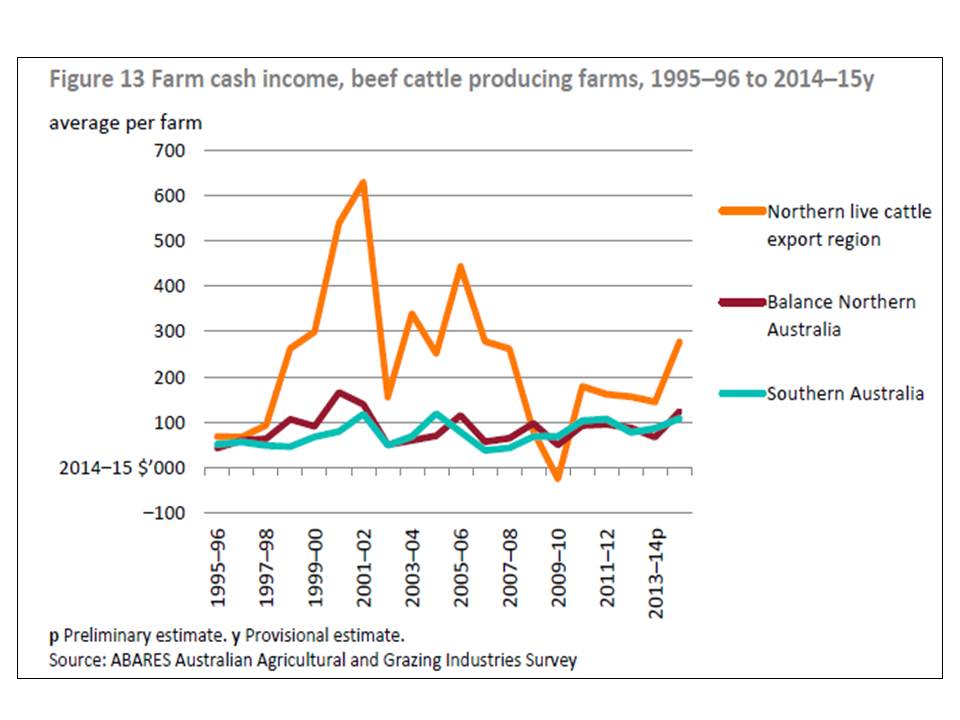

- Northern Australia beef cattle production is financially marginal for family businesses and attractive for corporate farmers with joint venture partners in Asian countries. ABARES/MLA’s latest data demonstrates this, figure 2. Commenting on the figure in its August 2015 review of the cattle industry ABARES/MLA said: “Many of the largest herd size farms in the northern live cattle export region are corporate entities. These farms dominate turn-off and performance estimates and typically have financial performance well above the average for other smaller herd size businesses in the region.”

Figure 2: Large corporates businesses have a dominant influence on the northern live export orientated beef cattle business cash income and profitability. Some smaller less profitable family businesses are selling out while economic conditions are favourable, as they are currently. Source: ABARES/MLA Australian Beef August 2015.

More family farmers as well as a few long-term corporate farmers, all of whom have suffered years of low cattle prices, are taking advantage of increased interest in purchasing cattle stations, especially from vertically integrated Asian companies who are more likely to process live cattle off-shore. A recent ABC Rural report demonstrated that 21% of 223 pastoral leases in Northern Territory are fully or partially owned by foreign businesses. Most of the new buyers over the last three years are Indonesian and Chinese businesses. A similar sell off to overseas buyers is taking place in Queensland as debt burdened family farms (average beef cattle farm debt in Queensland is $1.4 million) take advantage of higher land and cattle prices.

- Vertical integration of cattle production, processing and consumer marketing is far more profitable than selling cattle at the farm gate. Australia’s largest corporate cattle producer AACo demonstrated this when it changed business direction to become a processor and marketer of branded beef products and built

- Abattoir processing and quality assurance compliance costs are frequently quoted by Australia export beef processors as three times higher per kg of carcase in Australia than they are in competitor beef export nations such as USA and Brazil. Asian countries which are (or will become) major live cattle importers such as Indonesia, Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam and China, have even lower labour and QA compliance costs across feedlots, abattoirs, boning rooms and distribution channels.

- Labour availability and industrial relations are difficult issues in all of Australia’s cattle processing businesses. Companies are increasingly turning to labour hire firms to manage their labour forces. Some labour hire firms are under investigation for unscrupulous practices associated with working conditions, accommodation and pay rates especially with 457 Visa holders who are brought into the country to undertake jobs in abattoirs, which Australians are not prepared to do. Government and union oversight of abattoir worker conditions are likely to be far less rigorous in developing countries than they are in Australia.

- Value adding to beef cattle carcases and marketing branded beef is where most of the profit is generated in the value chain. As the proportion of middle income consumers increases in Asian countries, domestic Asian processors finishing and processing live cattle from Australia will have the logistics and marketing edge to take advantage of value adding the entire carcase compared to Australian processors who need to compete in Asian markets, mainly with the higher value beef cuts. While MLA data on offal value is limited it indicates each animal processed in Australia has an offal value of around $250. Offals are likely to have a higher value per animal when processed in Asian countries. The sudden rise in new live export markets such as Vietnam, and Thailand and which is about to happen in China, is testimony to this developing value adding opportunity.

Cameron Hall, general manager of Elders International Trading indicated what is happening in these countries when he said recently that many Chinese importers were constructing new purpose-built facilities to accommodate the Australian feeder and slaughter cattle that will come into the Chinese market. The same activity was happening in Vietnam as its imports increased from about 1000 animals in 2012 to 309,000 in 2014 – 15, figure 1.

In a February 2015 Beef Central article, Dr Ross Ainsworth described “amazing developments” in the Vietnamese and Cambodian live cattle importing sectors. He points out four large feedlots and two large western style abattoirs are under construction in Cambodia. What is particularly interesting is his description of who is driving these capital intensive developments.

“… the only players that can step in and start this type of large scale cattle project are wealthy entrepreneurs or large corporates that have the necessary political clout as well as healthy external cash flows to fund the long winded and capital intensive development of a cattle importing, fattening and processing project from scratch.

“Large, wealthy, well-connected companies from Cambodia, Malaysia, Vietnam, China and elsewhere in the region have seized the opportunity and stepped up with their capital and got started. Cambodia…has plenty of cheap labour, water resources and lots of agriculture producing significant quantities of waste products well suited to feeding cattle,” Ainsworth said.

Even live cattle export businesses are preparing for the new opportunities and increasing their involvement in off-shore beef cattle finishing (in feedlots) processing and retailing. For instance Elders International has interests in beef processing and marketing in Indonesia; and Wellard Rural Exports recently announced a 50-50 joint venture with the Chinese company Fulida Group to supply Australian cattle into China and market the beef produced.

Wellard’s chief operating officer Scot Braithwaite told Beef Central that “..Wellard’s business development strategy in China was teaming up with an established and highly regarded local company.”

Branding overseas processed products?

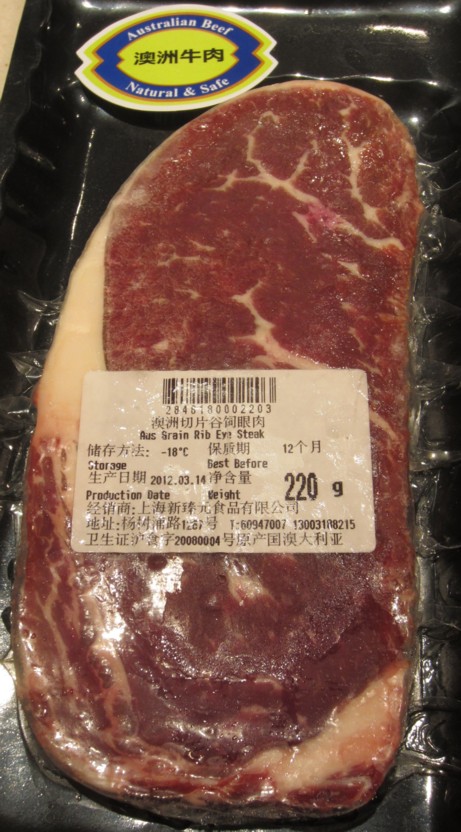

One of the unanswered questions about beef processed overseas using imported live cattle is how will it be branded – product of Australia or product of China or Vietnam or Malaysia? Given the reputation of Australia for safe, fresh beef, marketers are likely to claim it as Australian beef which will create reputation risk for beef actually processed in Australia under transparent and tight regulations.

How are the sweet cuts from Australian cattle finished and processed in overseass countries branded for Asian consumers?

Another unanswered question about Australian cattle processed overseas is to what extent will they compete with chilled beef processed in Australia. Beef is not part of the staple diet in Asian countries. In particular the most expensive primals are seldom if ever eaten at home but are becoming more popular in the food service sector traditionally supplied with chilled (and frozen) beef from Australia, New Zealand and the US. Secondary beef cuts and offals are sold in wet markets but even then at a premium price to chicken, pork and fish.

Sweet cut primals are Australia’s beef exporters most lucrative product. Their value on export markets could be undermined by an increased supply emerging from on-shore, lower cost processors supplying them at a significantly reduced price to the food service sector.

Figure 3: Once live exports exceed around 1.5 million head, the sector will be competing with south eastern Queensland and southern states for cattle putting more pressure on the viability of on shore processing. As well, the 30 – 40% of a carcase categorized as sweet cuts when processed off-shore from Australian cattle are likely to compete with Australia’s high value chilled and frozen beef exports.

For the time being Australian processors compete in the high value end of the market as supply remains short. As more live cattle are exported more sweet cuts from overseas abattoirs will compete with Australian processed beef in Asian markets. The situation will be exacerbated as an increasing percentage of live cattle come from eastern Australia’s Bos taurus cattle herd. (Under the new China Australia free trade agreement for live cattle import permits will only be issued for cattle from southern Australia because of a restriction surrounding cattle imports from the bluetongue virus transmission zone in northern Australia.)

How prices compare in Asian markets

While data on sweet cuts prices in Australia’s export markets is not available, an interesting analysis of Asian market prices for live export cattle processed overseas was recently outlined by Dr Ross Ainsworth in Beef Central.

He compared beef round (also called “thick flank”, a secondary cut in Australia) prices in wet markets, and in supermarkets with live steer purchase prices (imported and in China domestic cattle) and with broiler chicken from January to August 2015 in six major Asian live cattle importing countries. The data demonstrated:

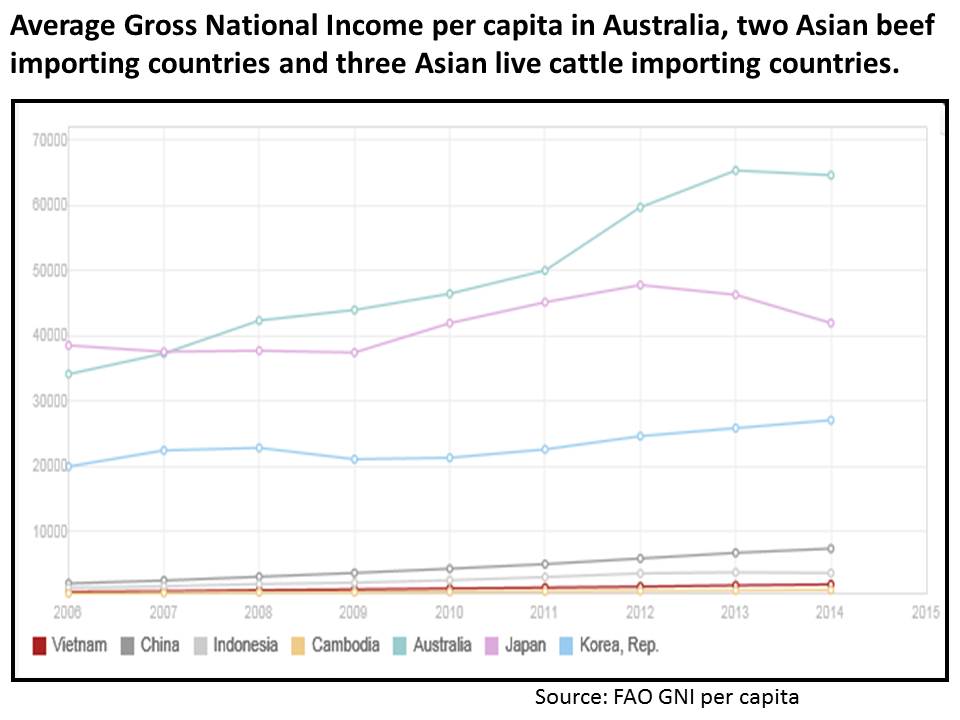

- Wet market prices have remained stable in virtually all countries despite a significant rise (around 20%) in live cattle prices over the period. This stands to reason as wet market consumers would generally have less discretionary spending money and if the price increased, they would shift to a cheaper meat alternative. For example in Jakarta wet market beef was generally A$10 – 11 per kg for round, while chicken was A$2 -3 per kg. Similar differentials occurred in China, Thailand and Malaysia. In the Philippines beef was about 50% cheaper in wet markets and supermarkets than in the other five countries because the live cattle imported are cheaper being mostly cull cows and bulls (compared with young finished or feeder cattle imported into the other countries).. In Vietnam wet market beef was approximately 40% more expensive than in Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia while the import cattle price was only marginally higher; it also had the highest chicken meat prices of the five countries. Given Vietnam has one of the world’s lowest average annual per capita incomes in the world ($1890 in 2014 according to World Bank), figure 4, it is difficult to understand who is buying beef at the prices quoted, A$14.60 in wet markets and A$16.70 in supermarkets.

Figure 4: Average per capita income in Australia versus two beef importing countries, Japan and Korea, versus three live cattle importing countries. Source: World Bank. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD/countries/VN-CN-ID-KH-AU-JP-KR?display=graph

- Supermarket beef round price were generally A$0.50 – 2.00 per kg higher than wet markets in all countries except China. In Beijing the supermarket price was A$3 – 4 per kg higher. This gives an indication of how value adding (branding) gives a greater return to processors/wholesalers. Unfortunately no indication was given as to the value of primal cuts in each country. Given these are generally consumed in the food service sector prices in excess of A$25 per kg could be anticipated.

- Across the six countries live cattle price represented between 20 and 40% of the supermarket price for beef round, with the highest margins (below 30%) being in Jakarta, Beijing, Shanghai and Ho Chi Min City. (It is unfortunate that no Australian commodities organisation has undertaken a comprehensive analysis of the value of the whole carcase from Australian live cattle when value added in the different destination countries). In Australia MLA regularly surveys the farm price as a percentage of the total domestic market value of a beef carcase; it is currently around 33%.

- Chicken meat prices in all six countries remained stable over the period and was generally 50% to 75% lower than wet market beef round prices.

Australia’s cattle population pegged

Another reason why live exports expansion will threaten Australia’s export cattle processing sector is that the national herd seems capped at around 12.5 to 13.5 million breeding cows. In southern Australia cow reproduction rates are high marking averaging 86% calves, but in the north where the majority of the cow herd is run, climate variability limits branding rates resulting in an average 71% over the past 20 years, figure 5. Turn-off has not changed that much from year to year but beef production does, as seasonal conditions dictate whether or not businesses hold or sell slaughter/feeder animals.

Figure 5: Despite a significant investment in technology and extension beef cattle branding rates in Australia have remained stable for the last 20 years. Source: ABARES/MLA Australian Beef August 2015.

While Australia’s beef cattle production has increased over the last 20 year, most of the increase has been generated from higher slaughter weights. For instance in 1990, the 8.4 million cattle processed in Australia produced 1.7 million tonnes of beef with the average carcase weight being 208 kg. In 2012 (before the Queensland drought induced sell-off began) 7.9 million cattle produced 2.1 million tonnes with the average carcase weight being 270 kg (ABARES Agriculture Commodities December 2014).

Given the natural increase of cattle is dictated by the cow herd, which remains moderately stable given Australia’s climate and competing interests for agricultural land, any increase in the proportion of cattle exported live is likely to put financial pressure on existing export abattoirs as numbers available for processing decline. The Top End stations which currently support the live export sector are virtually at their production limit supplying existing demand of approximately one million cattle..

Add in drought conditions in parts of Australia’s cattle breeding country, particularly in Queensland causing breeding cow numbers to drop to the bottom of their long term range, then the number of cattle available for processing is further reduced and a supply crisis is likely to develop in the sector. Cattle prices will be pushed higher as demand outstrips supply, but domestic processors’ costs of doing business will continue to increase with plants operating on reduced shifts. Lack of supply is already causing some abattoirs in Queensland to reduce operations as herd numbers significantly declined over 2013 – 14 due to drought.

The elephant in the live export room is likely to be what happens in China if the A$ remains at a significant discount to the US$ and the free trade agreement with China encourages significantly increased live exports. Talk of up to an extra one million head being exported to China over and above the one million currently going to Indonesia and other live export markets, will produce a radically different trading environment for domestic processors. Vietnam could also become a half a million plus live export destination.

This means live exports could jump from approximately 750,000 to one million head per year over the last decade, to 2.5 to 3 million young feeder and slaughter cattle per year in the next four years. That means live exports shift from taking around 10% of the young cattle born each year to around 30%

There are three possible scenarios for export processors:

- They continue to compete profitably by value-adding to beef cuts; introducing technical innovations and by reducing costs, especially labour in their own plants; and/or

- They develop joint ventures with Chinese meat businesses to inject capital here and guarantee consumer market access. Inverell, New South Wales livestock processor Bindaree Beef Group through its meat marketing business Sanger Australia completed a joint venture deal in September with Chinese company JD.com to market specialty chilled beef cuts on line to Chinese consumers. and/or

- They see a brighter business future by processing and value-adding to feeder and finished Australian cattle off-shore, the so-called “can’t beat them, join them” scenario witnessed in the car industry.

A recent Rabobank report assessing the Chinese beef market suggests that scenario three is not far off. Senior market analyst for the bank, Ms Chenjun Pan, said while Chinese consumers are becoming more affluent and have been purchasing more imported beef, the price they are willing to pay is now close to its ceiling above which they will return to greater amounts of pork, chicken and fish. Pan said price of protein is Chinese consumers’ primary consideration so live cattle importers and processors will be active as long as this does not become exorbitant. If price and cattle availability from Australia was favourable Pan said “… it will make a lot of sense to import live cattle. In China you can fully utilise every part of the animal and maximise the value”.

In ABC Rural’s review of cattle station ownership in Northern Territory, farmers involved were quoted as saying foreign ownership has been a feature of the Top End industry so there is nothing to fear from the investment taking place. While that is the case in Northern Territory because there is only one export abattoir there, as the cattle farm buy-up spreads into Queensland and foreign owners opt to finish and process their cattle offshore (in vertically integrated businesses) then a threat will emerge to east coast businesses processing export market cattle. That’s the significant difference between current foreign investors and those in the past, that is, the cattle become a basic commodity to be produced as cheaply as possible then processed off-shore, taking jobs and wealth creation in rural communities with them.

An additional scenario associated with greater foreign cattle property ownership in Queensland, is vertical integration on-shore with companies breeding, finishing (in feedlots) and processing their own stock. While this is preferable to finishing and processing off-shore, there is the possibility of more issues emerging with foreign nationals being employed on special visas.

In the long-term, if the live export trade achieves a significant proportion of Australia’s annual young cattle turnoff (greater than 25%) then export cattle processing on shore will become dominated by processing low value manufacturing cattle – cull cows and bulls. Even domestic market cattle processing comes under threat as most major processing plants have licenses to supply domestic and export markets. If that was to happen Australian consumers may end up purchasing beef in supermarkets and butcher shops that is imported from countries like New Zealand, the US and Canada. There is even the possibility of beef turning up on shop shelves that is sourced from cattle born in Australia but finished and processed in Malaysia, Vietnam and China!

That’s a prediction that Wellard Rural Exports Asia general manager Scott Braithwaite alluded to at a Beef Australia forum in May.

“What if the (cattle) processing industry follows the car industry or the steel-making industry and there is not an export facility operating in Australia by 2030. The efficiency and logistics of our northern neighbours allow it to be much more economically viable to ship the raw materials offshore to process. There is a strong possibility (live exports) could become the dominant market for producers,” Braithwaite said.

Live export companies are involved in joint ventures with Asian companies to finish and process Australian cattle overseas. It is in their interest to have live export cattle numbers increasing.

Take home message

Investment in cattle feeding facilities, abattoirs and boning rooms taking place in Asian countries importing Australian live cattle suggest the trade will shift from one which suited Top End farmers to one sourcing cattle from all states and directly competing with Australian feedlots and export licensed abattoirs. The abattoirs will find it increasingly difficult to operate profitably.

As well, it is likely that the export abattoirs’ established high value beef markets across Asia will have to compete with lower priced products from Australian cattle finished and processed off-shore.

Farmers outside the Top End supplying live export cattle may initially gain financially from the competition generated but will be isolated from genetic carcase traits feedback and value adding opportunities associated with on-shore feeding and processing. They will also be more exposed to any financial or other crises that affect businesses in Asian countries. The latter will be more acute if Australia’s on-shore feedlots and abattoirs sector declines in the face of the live cattle exports increasing above two million head annually.

END

A very interesting read. Though I do think you have missed the fact that profitability at the grassroots level in the beef industry must increase if producers are to survive. Without the competitive factor of live export then the entire beef industry will suffer and thus overall herd numbers will decline as profitability is not achieved or properties run at a loss. There are over 6M head of cattle across North Australia with the numbers up here increasing while the south are stagnant or decreasing as other land uses become more profitable. The figures from ABARES that estimate the average calving % is 70% across the north would be a stretch at best. Maybe some of the better fertile areas, most certainly not across the entirity. There is hugh room for productivity improvement in the north, in areas of nutrition, calving, even dog damage control, add to that if we could put in better pregnancy detection, or vaccinations that could spay culls the productivity in turnoff of animals could increase significantly from the very same base herd we have now. With the AACo abattoir enabling better management of cull animals that will improve heifer and overall female management in the long term of the herds. There is room enough for live export to increase and Australian herds to maintain meat processors but meat processors have to actually pay a fair price and then if they can’t or won’t do they expect producers to give their stock away. Of course the overriding factor for all producers is weather. Drought has played its hand in the last couple of years. There are many who thank their lucky stars LE was available because when the processors couldn’t handle the capacities they didn’t increase shifts they simply held back taking in animals, a cost the producers were expected to wear. Regards Jo