New attitudes to native grasses for win-win outcomes

Precede:

There has been a paradigm shift in the way Ian Locke ‘Spring Valley’ Holbrook NSW manages and grazes the steep native pasture hills on the property. With the help of thorough records he has been able to demonstrate why the new approach is benefiting financial performance and environmental outcomes on the property. This is his story of change.

‘Spring Valley’ is largely sown to highly-productive phalaris and sub clover pastures with some ‘feed gap’ pastures such as lucerne, ryegrass and forage rape. Traditionally, spring rains are very reliable (10% of springs fail) and autumns not so reliable (60% of autumns’ fail).

We grow 80% of our pasture in spring and therefore our livestock systems are designed around calving and lambing and growing out animals in spring to best match the pasture production curve.

The property is 1,520 ha with around 1,400 ha usable for grazing livestock of which around 15% is native pasture on hills and the rest arable country mostly sown to perennial pastures, annual pastures and crops. The soils and landscape on the property are highly variable and include alluvial and heavy clays on the flats to granite-based slopes and rocky hills. The soils are naturally acidic (pH = 4.0 – 4.5 in CaCl2) and inherently infertile (7 – 9 mg/kg Olsen P). Nevertheless the country is very responsive to inputs of lime and superphosphate.

Years of sowing the latest cultivar of cocksfoot, fescue, chicory, plantain and perennial ryegrass, only to see them wither and die-out in the droughts has taught me that the best pastures are those that persist. Good ol’ Australian phalaris and sub clovers, well fertilised and a grazing system allowing paddocks to be rested they do not just survive, but thrive.

While 80% of the property could be described as arable, much of the decomposed granites are seen as too fragile to sustainably crop. Grazing crops typically include early oats and triticale, usually as a weed control tool to later establish a permanent pasture.

In the late 1990’s, we sprayed-out and drilled grazing crops into the semi-arable parts of the native-based pastures. I now regret this, as I didn’t fully appreciate the existing native perennial resource base that was in fact a good, low-input pasture. Although sowing increased production in the short-term, it was unsustainable in the long-term with the ongoing competition from annuals, particularly broadleaf weeds, adding to the ongoing costs and declining long-term production in that class of country.

Enterprise mix

The cattle and sheep enterprises are driven as hard as we can with a focus on our per hectare performance rather than production per head. In the seedstock Poll Hereford beef enterprise (70% of carrying capacity) we differ from most studs in that we place a large emphasis on raising cattle under commercial stress conditions believing that the genetic outcomes are more applicable to our commercial client. A flexible backgrounding enterprise is run from July to December, if the season permits, utilising surplus spring feed.

Over the years, we shifted away from wool and Merinos to a prime lamb flock (LAMBPRO -a self replacing maternal flock comprising 30% of carrying capacity). I always felt that the wool flock made the most money when we had a high proportion of wethers to keep cost /kg wool produced down. The drought years, unfortunately, saw the wethers often sold as they were the shock absorbers in the system. This, combined with struggling wool prices and increasing sheep-meat values, have seen us shift to a prime lamb enterprise selling store lambs.

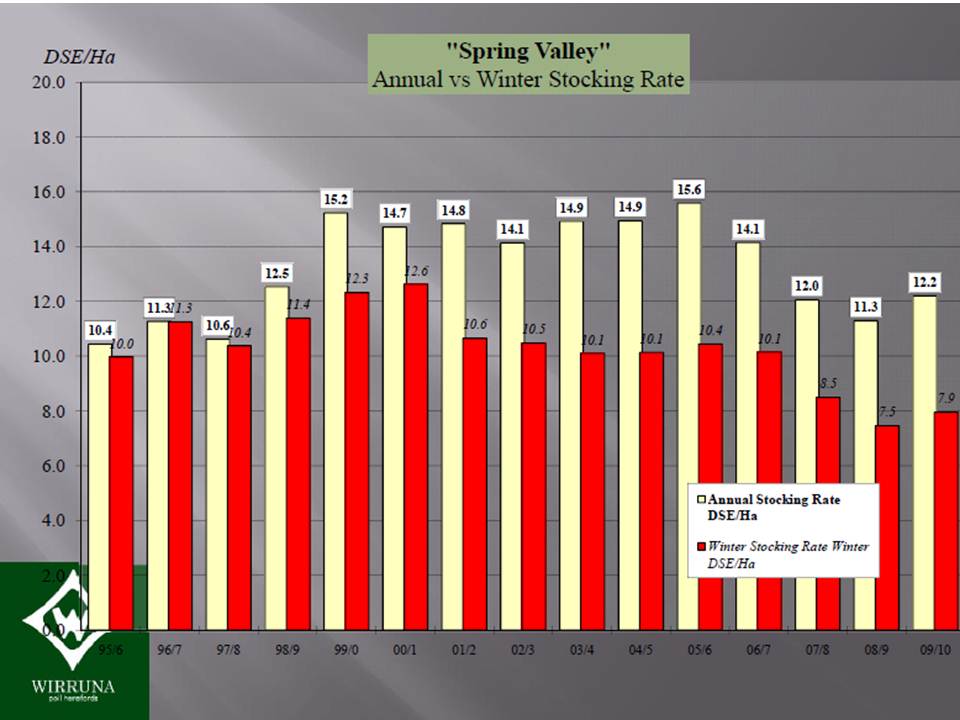

The fact that the pasture requirements of a spring-lambing and highly-fecund ewe far better matches our pasture growth curve, in contrast to a Merino wool flock with a high proportion of wethers, has also improved our ability to get through the tough autumns. As exhibited in Figure 1, the gap between winter stocking rates and what we carry on an annual basis has widened.

Figure 1: Annual versus winter stocking rate on Spring Valley since 1995.

The role of the native country

It used to be that the native country bore the brunt of our high stocking rate regime, especially in the lean feed months. I would use aeroplanes to fertilise the hills (80 kg single super/ha) to increase feed quality and quantity, graze the hills bare, typically with dry sheep, and then I would need another plane to fly on chemicals to control the rampant broadleaf weeds (mainly Paterson’s curse) that were establishing rapidly and thriving on the bare ground.

This old regime was unsustainable where $13.67/DSE in pasture costs was being spent on a dry sheep enterprise returning a Gross Margin/DSE of around $12, table 1.

Table 1: Old management regime costs for maintaining stocking rates on native pasture.

| Fertiliser | Super @ 7.2 kg P/ha @ $4.44/kgP | $31.97 |

| Aerial spreading (March) @ $11.50/ha | $11.50 | |

| Sprays | Chemicals (MCPA/Igran) @ $13.08/ha | $13.08 |

| Aerial spraying (July) @ $20.00/ha | $20.00 | |

|

Total cost/ha |

$76.55 | |

| Total cost/DSE @ 5.6 DSE/ha | $13.67/DSE |

The native grasses and the country were suffering! Particularly over the tougher summer and autumn periods, the bare ground was also exposed to possible storms with no protection against soil loss through erosion.

Improving the pasture species to improve pasture quality or liming the hills could never be economically considered. Clearly, something had to change with our management of the hill country and this required us to recognise the value of the native perennials that already existed, and design a system better able to protect that resource and at the same time was of benefit to overall farm productivity.

The ‘New Regime’

With the experience of beginning to ‘crash graze’ various tree lots and set aside areas when the trees were large enough to be protected from stock, and with scrutiny of some ‘holistic grazing systems’, we became convinced that we could still maintain the production of our native country and totally cut the inputs by grazing with large mobs of stock at only certain times of year.

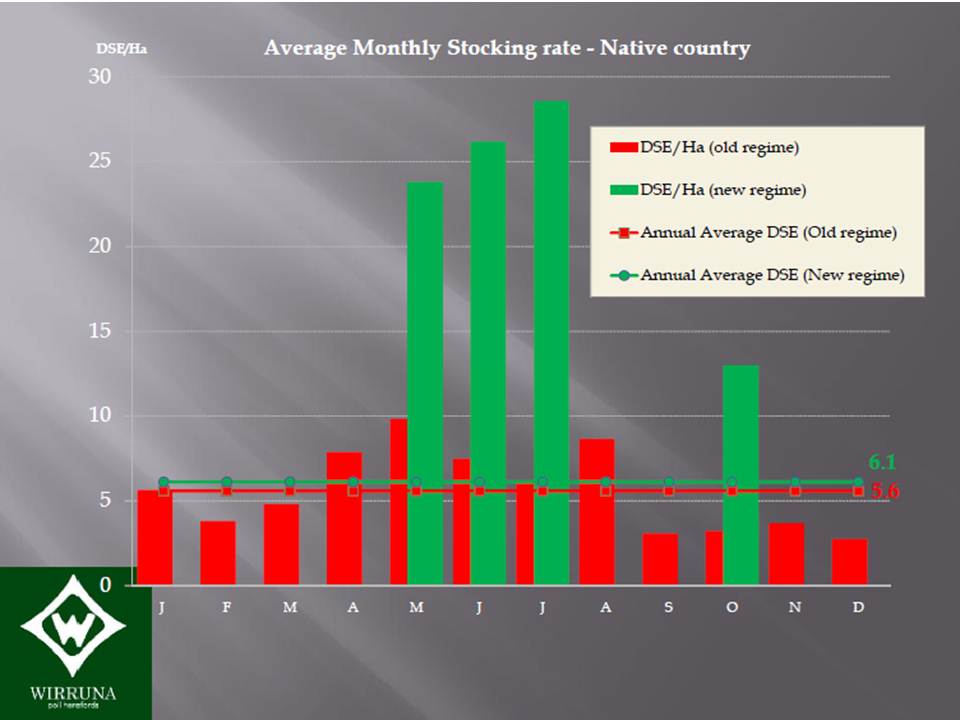

As shown in figure 2, the new regime involves totally resting the hill country from late spring through to autumn, when the predominantly summer-active native plant species, such as red grass and wallaby grass, are allowed to grow and set seed without any grazing pressure. Then, some 500 spring-calving cows and heifers are let into the country in mid-May where they chew back the mature and mostly low quality standing feed. The cows are pulled out in the 3rd week of July about one month prior to calving.

Figure 2: Average monthly stocking rate on native country – old regime versus new regime

After a further three months rest, sheep (or trade/backgrounding cattle) are introduced in late October to utilise higher quality native grasses, such as Microlaena, and to heavily graze the exotic annual species (clovers, broadleaf weeds and grasses). In turn, this creates space for the early growth of summer-active native perennials.

The new management regime of the native-based pastures looks to be benefiting the hill country with excellent cover for most of the year, especially over the summer period when the higher likelihood of intense rainfall events could damage exposed soils. Instead, we would perceive better moisture retention, healthier summer perennials and a growing diversity of plants. The lack of bare ground over autumn is also inhibiting the dominance of broadleaf weeds allowing the natives a better chance to recover.

The most exciting feature of the new hill country grazing regime is the whole farm benefits derived from deferring grazing on the high input perennial pastures during the critical annual grass and clover establishment and first phase perennial grass growth immediately following the autumn break. During this time, stock are let into the hills that is effectively a ‘winter haystack’ of low-quality feed and this hill country living is perfect for the fitness of spring-calving cows and heifers. Studies in the USA have demonstrated that there may also be additional stock health benefits by having a more diverse selection of feed on offer

Additionally, the deferred grazing of the phalaris and new pastures, to allow them to gain sufficient leaf area, on the improved country following the autumn break has huge benefits to the resultant late-winter and spring productivity of those ‘autumn-break rested’ pastures. Also it benefits the persistence of our phalaris pastures!

Is it Sustainable?

Anecdotally, the system feels more sustainable. Encouraging native perennial plant species that are exceptionally tolerant of drought, low soil pH and poor fertility while maintaining cover, retaining moisture, protecting soils and promoting biodiversity all makes sense.

It is possible that we are living off the residual phosphorus of the previous regime and that eventually the native-based pastures will ‘crash’ in terms of production if we do not maintain fertiliser inputs. Nevertheless, I am adverse to relying on fertilising the hills and instead I wish to see where we can sustainably manage these pastures.

If the hills end up crashing to a sustainable 2 DSE/ha over the long term without any additional fertiliser, I would certainly have to reassess supering to maybe once every two or three years to carry the 5 DSE/ha I know I can carry on the hills with fertiliser. I suspect that the low-input pastures (the new regime grazing) won’t crash to that extent. I am much keener to put super on the good pastures and better assess what the native country can carry sustainably without fertiliser over time.

Take home message

After years of fencing the farm according to land class and building productivity through pasture improvement and fertiliser applications, the native hill country became the last frontier.

At the beginning my approach was to fly on superphosphate and utilise anything extra that grew! Over time, it became clear that this approach was unsustainable at both the economic and environmental levels.

By recognising that:

· tactical grazing can favour some of the key native species,

· the native perennials have value in a low input pasture system, and

· we can integrate the native based pastures in our overall farm system to the benefit of our higher gross margin cattle and prime lamb enterprises, we now have adopted a regime of strategically grazing the native-based pastures at times that suit their regeneration and allow better management of the productive, improved pastures that are the powerhouse for our enterprises.

This is done at no downside cost to the annual average DSE carried on the hill country and in fact, saves previous fertiliser and weed control costs associated with managing the country for higher production.

Find out more

Ian Locke locke.ian@bigpond.com

.