Lambs and rainfall – challenges and successes over summer and autumn

An update on Moffitts Farm by Patrick Francis

As autumn comes to an end it is interesting to review activities and outcomes on Moffitts Farm over summer and autumn 2014. What stands out is how our “comfortable farming” system demonstrated resilience under the lowest summer rainfall we have experienced since we started it in 2000.

The resilience built into “comfortable farming” produced the following outcomes:

- No supplementary feed was needed for adult ewes and replacement ewe hoggets.

- The adult ewes improved their body condition score post weaning in late December and were in condition score 3 for joining in mid March. Ewe hoggets were in condition score 4 at joining.

- Our steers continued to gain weight until end of January then held weight until sold to JBS in early March. We took the decision to sell them despite being approximately 60 kg lighter than achieved in other years as the dry conditions persisted. All steers met the grid fat score target and 90% graded MSA.

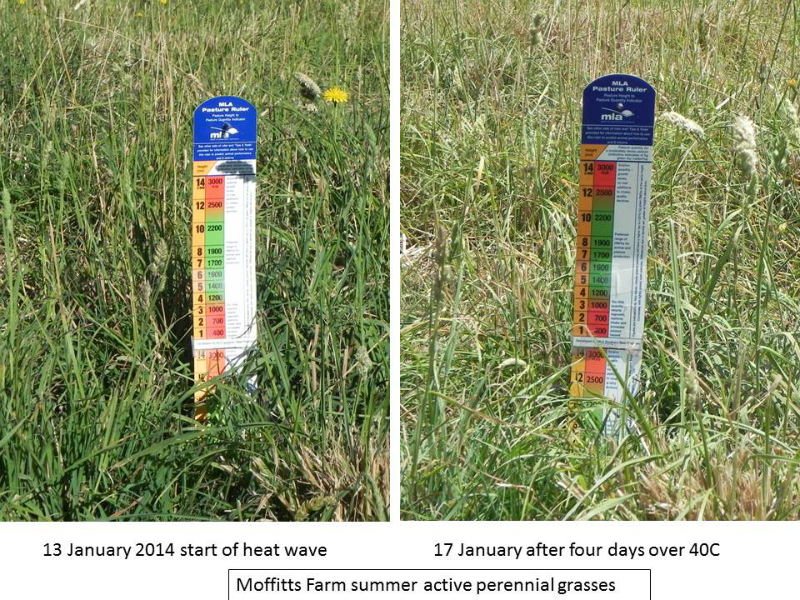

- Pasture dry matter (DM) levels were maintained above 3000 kg per hectare with one exception, a summer active tall fescue paddock, reduced to 2000 kg DM per hectare. This level of dry matter is important not only for livestock feed as standing hay, but also for ecosystem protection, that is protecting the soil and the soil food web it contains. A great example of how important maintaining dry matter levels is shown in figure 1 which shows the impact of 40C plus temperatures on four consecutive days on summer active perennials.

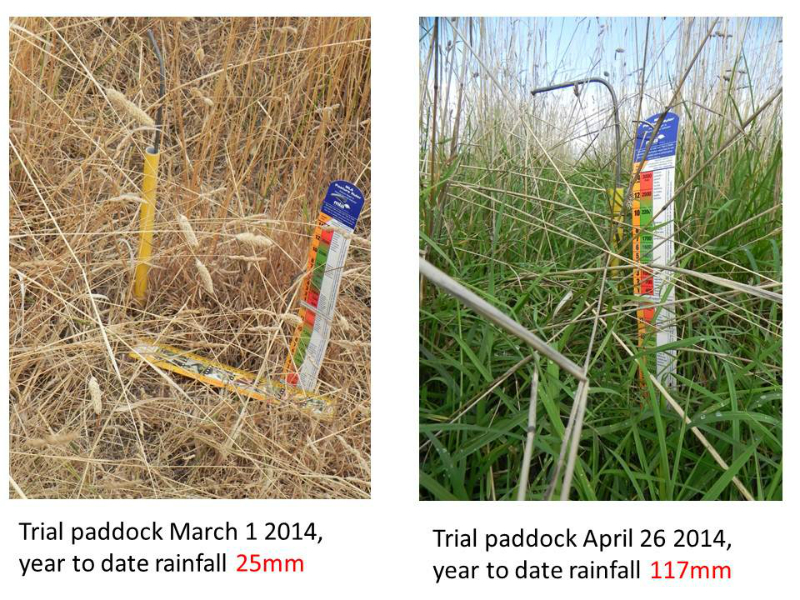

- When rain finally occurred in late March (21mm) and 10 days later on 10 April (50mm), the impact of dry matter level and protection it gives to the soil food web was spectacular. We anticipated that this was the perfect season to demonstrate just how well our pastures respond to rain so we started taking movie film each week at two pasture sites (one tall fescue, the other cocksfoot) starting in early March. It demonstrates how a pasture can transition from virtually zero green dry matter per hectare to 3000 kg green dry matter per hectare in four weeks, figure 2. And that’s on top of 2000 – 3000 kg of previous season dry matter. Such a result is achieved as a result of rapid nutrient mineralisation of organic matter by soil microorganisms which feed the plants. Remember we are protecting a total soil carbon resource measured at 4 – 5% (organic matter level of 7 – 9%) and no artificial fertiliser has been applied to the paddock since 2000.

Lamb feeding

The combination of a number of factors over summer encouraged our decision to try supplementary feeding weaned lambs for the first time. Firstly, lamb prices began to rise sharply in January from around 400 cents/kg carcase weight to 500 cents/kg. Secondly, the dry and extremely hot conditions meant while there was plenty of dry matter in the paddocks, its crude protein (CP) and metabolisable energy content were not sufficient to grow lambs, which require a minimum of 16% CP and metabolisable energy (ME) above 12 MJ/kg.

Our objective is to sell all lambs by mid June at weights above 40 kg live weight or 18 kg dressed weight. Average weaning weight on 30/12/13 was 25.5 kg. Without supplementary feeding on pasture with low CP and energy levels we would not achieve the desired sale weight or have to hold onto lambs over winter which would put pressure on feed availability for pregnant ewes.

A third factor which influenced the decision to supplementary feed was the availability of ‘lick’ feeders manufactured by Ballarat company Advantage. These appealed to me because you can control lamb grain or pellet consumption per day. This is particularly important to help prevent grain sickness but also to ensure the lambs don’t substitute grain for pasture. A major issue with the economics of supplementing grains on animals grazing pasture is that they will eat as much grain (or silage for that matter) in preference to pasture, especially when pasture digestibility declines. In other words, grain, pellets and silage are more attractive to them than pasture once pasture quality declines.

But with our summer active species which retain a green pick and respond quickly to summer rain, we didn’t want animals concentrating on supplement and not eating pasture. The lick feeder provided the means to keep the balance between consumption of pasture and supplement, figure 3.

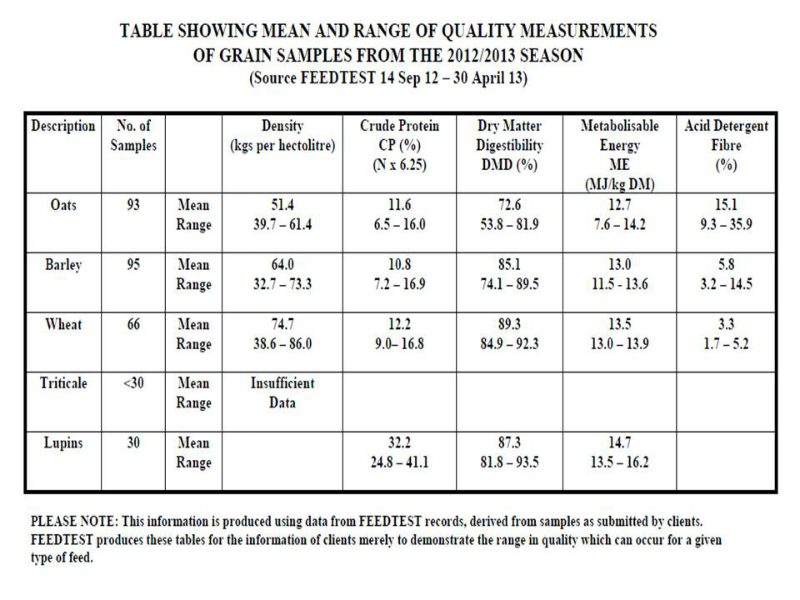

The choice of supplement was between a grain such as oats and a commercial lamb finisher pellet. The pellets were approximately 20% dearer per tonne but have the advantage of a guaranteed nutrient analysis, that is a crude protein of 16% and minimum metabolisable energy (ME) content of 12MJ/kg. In contrast no supplier provided an analysis of cereal grains and data from Feedtest shows cereal grains have enormous variation in nutrient content, Table 1. This means on a cost per kg of protein or ME, pellets can be less expensive than many cereal grains.

Table 1: Feedtest analysis of grains shows the wide variation in nutrient contents. Without knowing a grains nutrient content it may mean lambs are being fed a sub optimal supplement. Source: Feedtest.

As it turned out summer rain didn’t happen this year so the decision to supplement with pellets in an Advantage lick feeder was sound in terms of both growth rate and economically . I estimated we could spend $25 per lamb on pellets and make a profit on feeding. This decision became even more attractive when heavy trade lamb prices rose to 600 cents per kg dressed weight by the end of March.

With the help of Seymour Ag who sourced quotes from different lamb finisher pellet manufacturers we settled on the Coprice product in bulker bags (800 kg). These were delivered to Seymour Ag which in turn delivered them to Moffitts Farm as required. Our experience with Coprice had one major shortcoming, despite repeated requests, the company would not provide a certificate showing the list of ingredients in the ration. For quality assurance and lamb market transparency purposes having a list of ingredients can be important, especially if selling to a boutique outlet. For instance, if canola meal was an ingredient, knowing if it was sourced from a GM canola or conventional canola would be important to some customers and consumers.

We uncovered an issue with feeding pellets in lick feeders, that is pellet hardness. As animals lick pellets out of the narrow opening they tend to breakup with the fines blocking the flow. The fines need to be scrapped out every 48 hours. Advantage Feeders is going to speak to feed manufacturers about increasing pellet hardness to help overcome this problem. Overall the Advantage Feeder worked extremely well in terms of controlling feed intake and preventing any wastage. It is also extremely easy to adjust the lick opening.

An unintended outcome of this year’s supplementary feeding program has been animal contentment. The lambs became increasingly at ease with people checking the feeder and adding a small amount of feed to open trays adjacent to the self feeder. This was done to help overcome shy lambs which were reluctant to eat from the lick feeder. This contentment produced two outcomes, firstly lambs were easy to shift into a new paddock – they simply followed you in; and secondly they were not stressed by yarding and I would anticipate meat quality would be exceptionally high.

We sold the heavier ewe lambs to a neighbour who wanted them as future breeders. We organized selling wether lambs direct to Hardwicks abattoir in Kyneton, 30km from Moffitts Farm, figure 4. This arrangement worked well as we could deliver them in our own trailer, in numbers which suited us with a set price based on carcase weight and fat cover, and selling costs are minimised to the MLA levy only.

Pellet supplementary feeding stopped in late April as remaining lambs were grazing 3000 kg green dry matter pastures.

The decision to feed lambs takes current and future paddock feed into account. By feeding we began selling lambs in early April and finished in May. Without feeding in such a dry summer the lambs would have not grown sufficiently to sell until June. This would put pressure on our system which likes to grow a bank of feed over winter to coincide with ewes increasing feed demand through pregnancy and lambing in mid September. Our ewes move from being the equivalent of 1.3 dry sheep equivalents (dse) after weaning in December to about 3.5 dse with twins in September.

We also contend that a bank of pasture for lambing ewes is not only important for mother’s immediately accessible nutrition, but also for lamb survival, figure 5. The latter for three reasons, the lamb has protection from cold winds, secondly the ewe has large quantities of pasture all around so has no need to move away from the lamb(s) looking for feed, and thirdly the ewe has a relatively private birthing area so there is less opportunity for mis-mothering happening.